The 2008 global financial crisis: preconditions, reasons and results

This article was written by guest author Alisa Topchiy

Global financial crisis! Sounds scary, doesn’t it? Many people (hi, boomers!) remember just how devastating the 2008 crisis was. It swept like a hurricane across the planet. But if you look back at the situation more closely, it becomes clear that it was all a “comedy of errors”. Although, as you can imagine, few were laughing at the time. Gen-Z were children in those days, and most likely didn’t even notice the crisis at all. But it’s important to know about such critical events of the past in order to learn from the mistakes and be ready if something like that were to happen again (let’s hope it won’t).

How it all began...

Before we dive into the financial crisis horror story, let’s remember the most basic law of economics — supply and demand. According to this law, if the demand for a commodity rises, so will the price. That’s a crucial point: remember it.

So... Our story begins in the year 2000. That is when the countdown to the collapse began. Over the first six or seven years of the century, house prices soared by almost 90%, whereas in the 1990s, the average growth had been just 20-25%. Very strange, don’t you think?

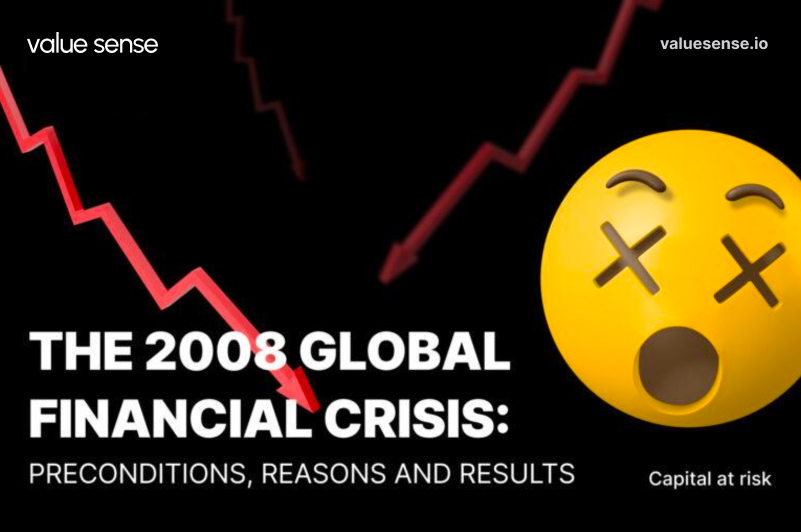

So, what could have led to such a fast rise in prices? Had the population grown, leading to an urgent need, a higher demand, for houses, and had prices increased as a result? Sounds logical. But let’s look at the statistics.

When we look at the data, we can see that the population did grow — but only by 6.6%. That hardly seems like it could have led to the crisis of such a large scale, so this assumption doesn’t seem to work for our purposes. Let’s give it some more thought.

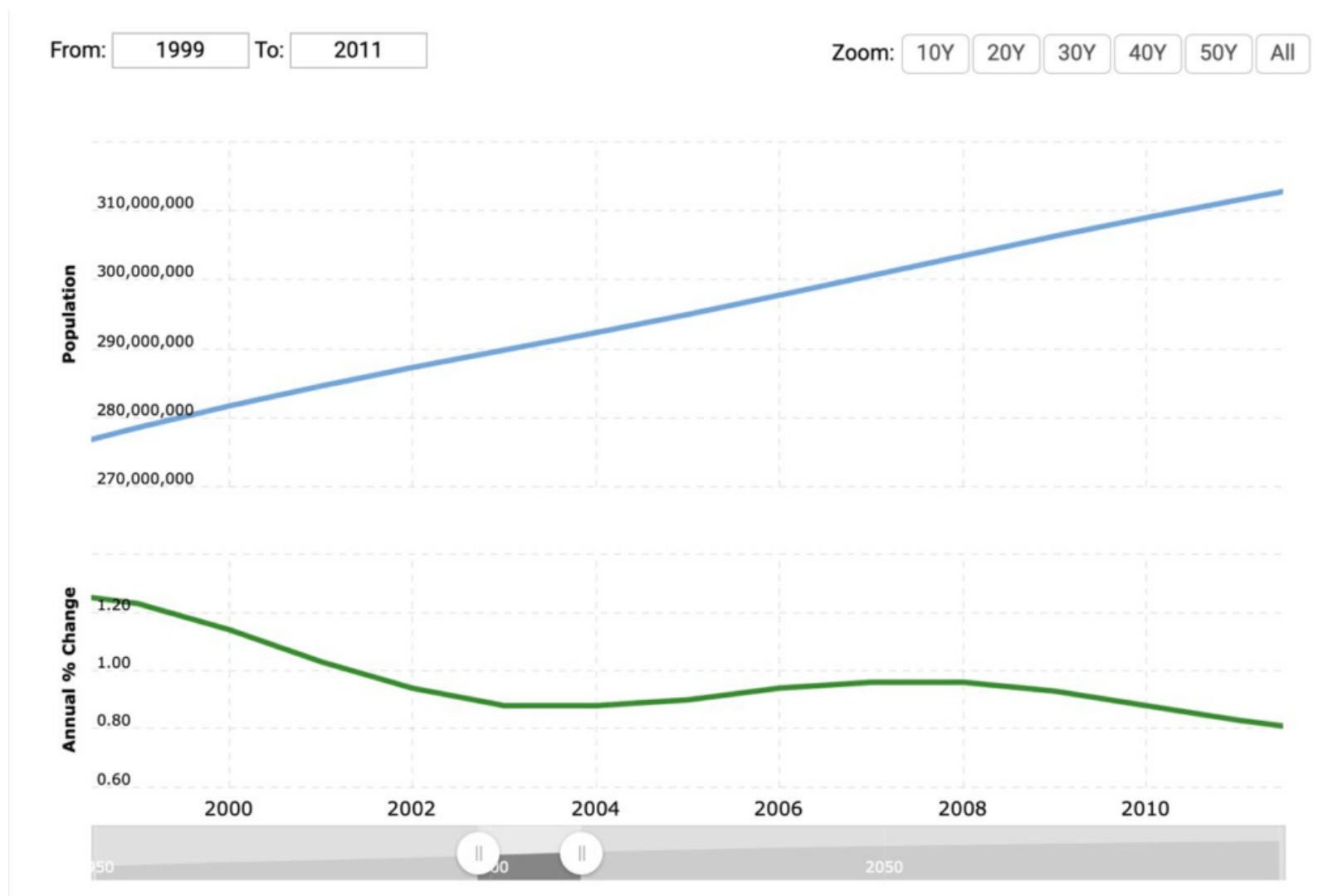

Perhaps incomes had increased, and more people had decided to buy a house, since they finally had enough money to do so.

But if we turn again to the statistics, we find, on the contrary, that the average family income in the US during that period decreased. In 2006, the average American family began to earn on average 2% less than in 2000. We’re wrong again.

What else could have happened? Did builders stop building new houses, causing a shortage that drove prices up? Did the X-Men’s battle with Magneto destroy too many houses?

No, nothing like that happened. People did not become richer, the population did not grow much, but prices still skyrocketed by 90%. So what did happen? What on earth was going on?

Well, the situation there was much more interesting than any of these assumptions. What led to the 2008 crisis can truly be considered a “comedy of errors”, in which everyone participated: ordinary people, banks, the state — just as with the Porsche and Volkswagen story.

So, here’s the horror story of the financial crisis, just in time for Halloween...

Let’s start with the terms and conditions of mortgages in the US.

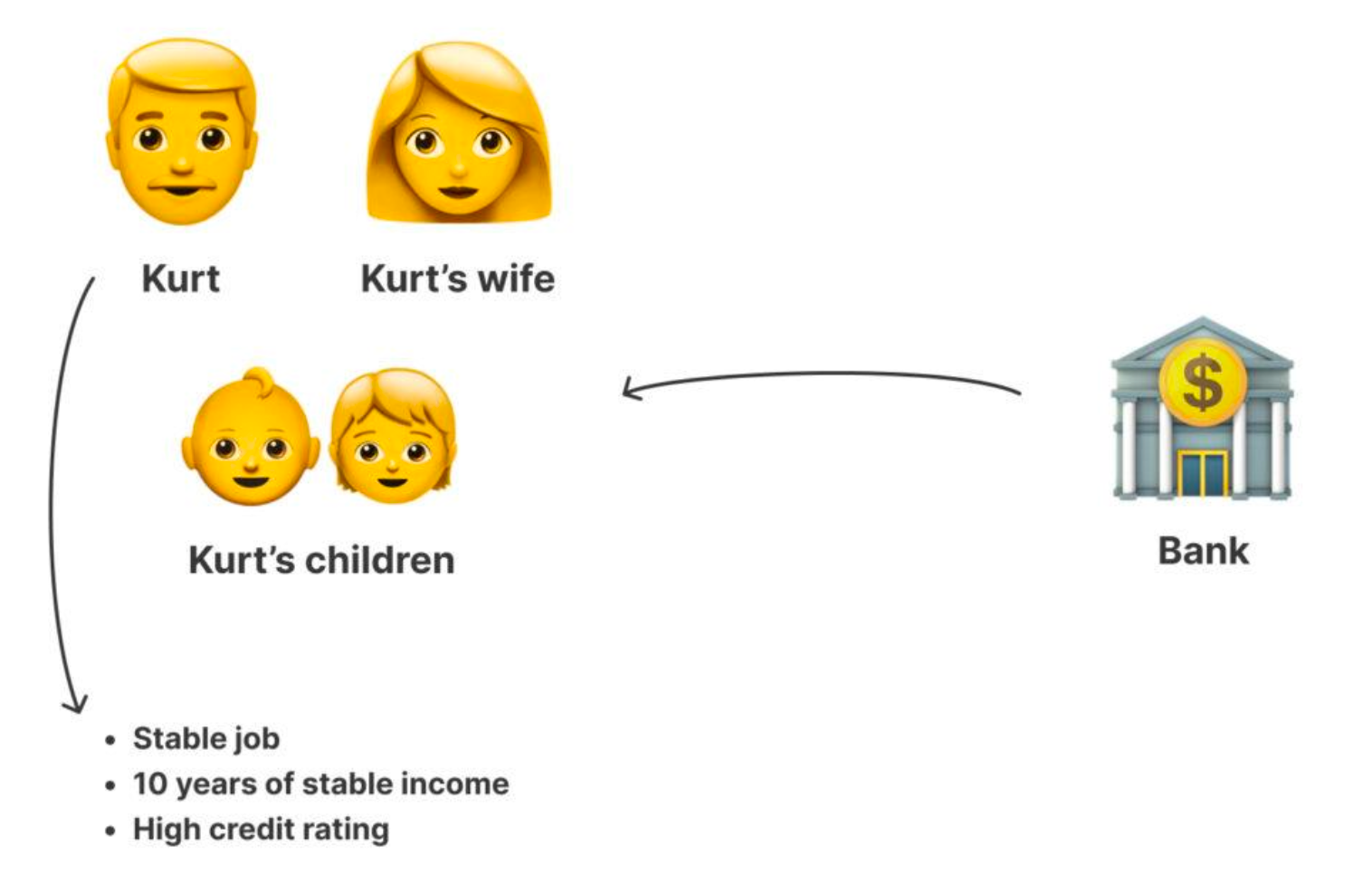

Before 2000, in order to take out a mortgage and buy a house in the United States, one had to:

- pay 25% of the value of the house;

- have regular work with many years of net salary;

- have a high credit rating.

All of this was carefully checked, and so cases of non-payment of mortgages were extremely rare.

However, by 2004-2005, things had changed:

- No prepayment was needed

- Employment history and income were not being checked

- Credit rating was not important

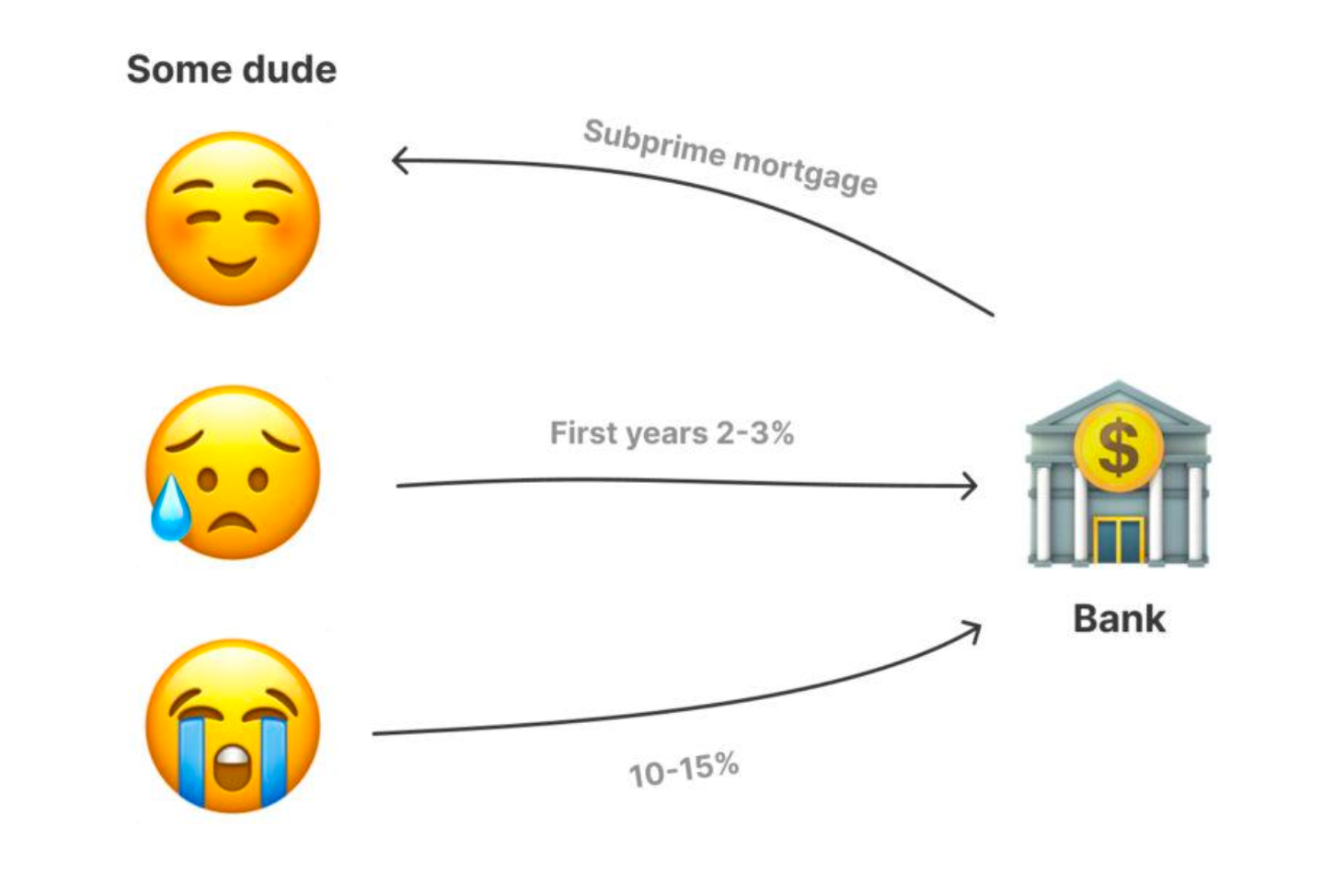

In addition, those who could not afford a regular mortgage could access a so-called subprime mortgage. These were loans with low rates (say 2-3%) in the early years that later could grow to reach 15% or even 20%. Such loans were a bomb planted right at the heart of the global economy. And the countdown to the explosion began.

Was this some kind of general madness — or was there a plan?

Surely you’re now wondering: “What were the banks thinking? Were they thinking at all?” Why give out loans almost for nothing to people who would either struggle to pay them back, or wouldn’t be able to pay them back at all?

To answer this question, we need to go back even further into the past.

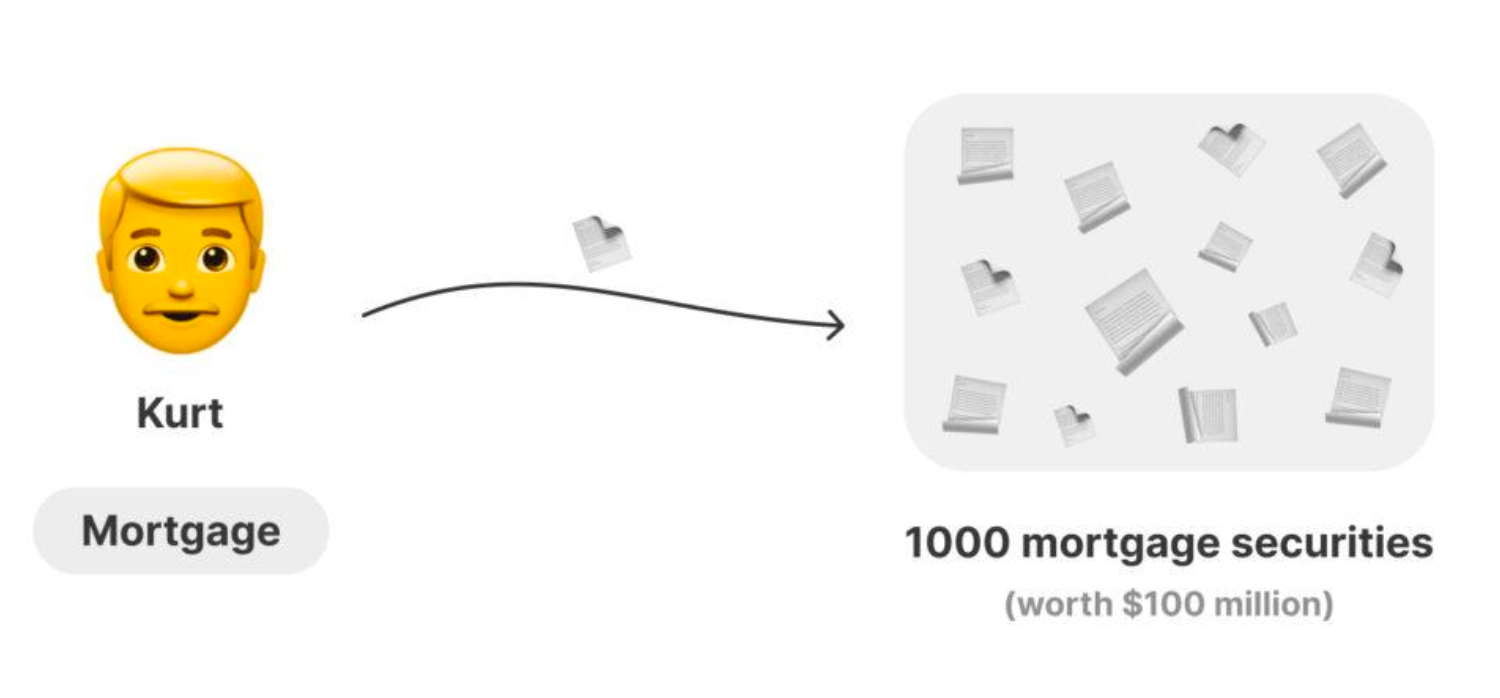

Let’s take a look at the structure of the mortgage market in the United States. Since the mid-20th century, most mortgage loans in the United States had been issued by semi-government mortgage agencies. They came up with the idea of issuing and reselling mortgage securities on the stock exchange, so that, back in the 1970s, a US citizen had to pay back their mortgage not to a bank, but to a third-party investor. The system of checks and balances provided guarantees to those who bought housing on a mortgage, and to the state and third-party investors. Mortgage securities were very reliable, but did not bring much income, and therefore were not in demand. The conditions were tough, so mortgages were mainly taken up by responsible citizens who paid consistently and on time. Mortgages were secured by deposits, so that if the debt was not repaid, the house was taken away and sold at auction.

Over time, private companies began to buy mortgages from agencies and issue their mortgage securities. Furthermore, in the 1980s, the Reagan administration and the US government decided to gradually loosen the regulation of the financial and banking sectors, towards minimal regulation of the US economy. New financial instruments and forms were introduced, and the old ones faded away year after year. In addition, in the late 1990s, the ban on combining commercial and investment banking, which had been in effect since the Great Depression, was lifted. Seeking ever greater profits, banks began to invest in riskier assets, and in the ’90s, the securitisation of mortgage securities began to gain popularity.

Insurance issues

In addition to other stabilising mortgage securities, there was one further factor — insurance. The original government agency mortgage bonds were insured by a different government agency, so that as mortgage securities of investment banks and funds became popular, the question of who would insure them arose. This is where private companies got involved. It seemed to everyone that it was dramatically profitable to insure mortgage securities, because the mortgage was always extinguished and paid regularly (of course), which meant that the profit would increase, and the risks would be minimal.

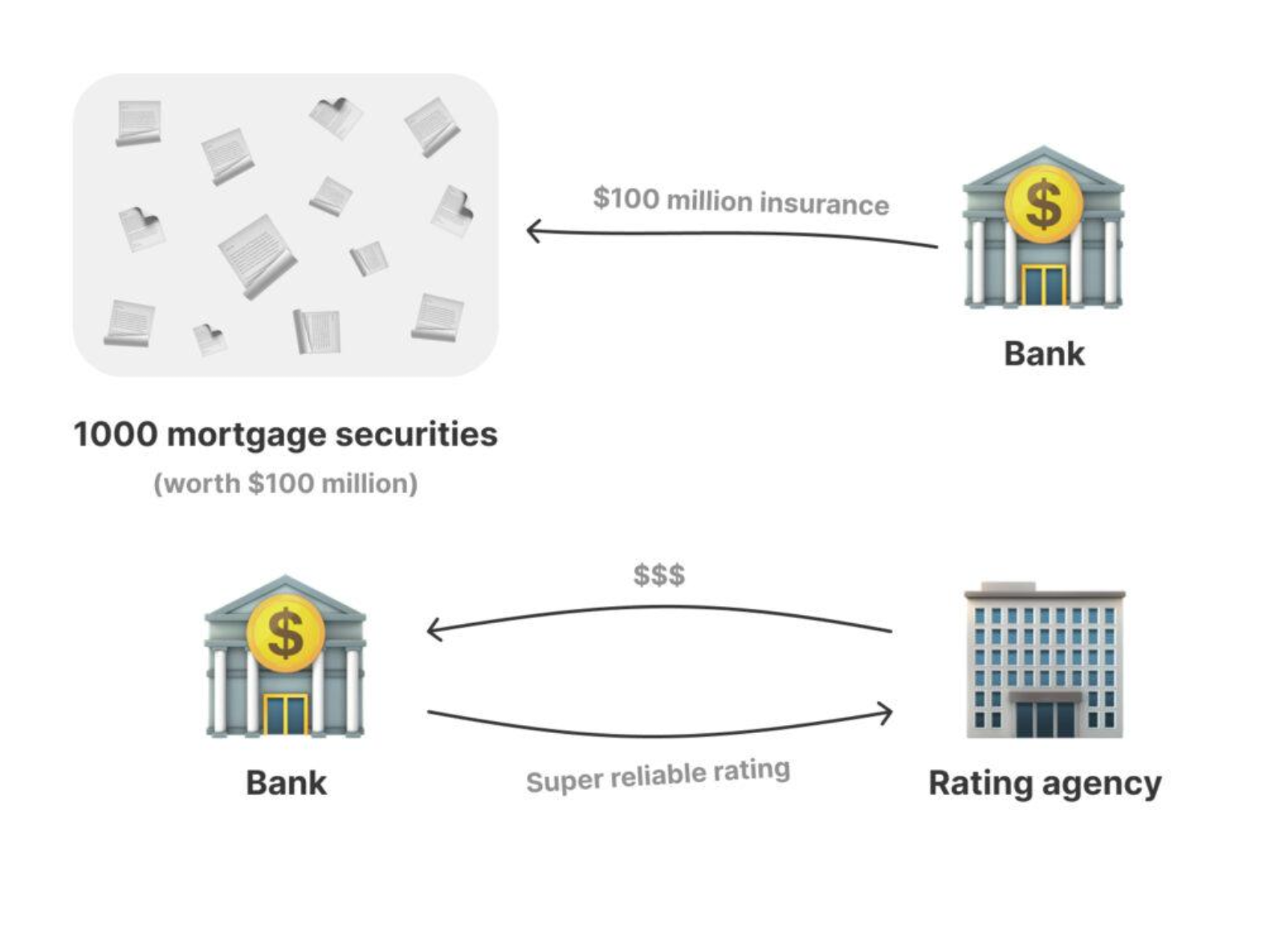

Rating agencies also got involved in this chain of communication between borrowers, banks, insurance companies and investors. Ratings agencies are special organisations that determine which instruments or assets are reliable or worth investing in (even if they don’t offer high returns), and which are not very reliable but carry a higher chance of earnings. They have existed for over 100 years, not only in the United States, but all over the world. Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch Ratings are well-known rating agencies.

These rating agencies were required to rate new mortgage securities before they were sold to investors. Almost always, the rating of such securities was AAA (Triple-A) — that is, extremely reliable, just like the debt obligations of the US government, for example — or BBB medium reliability.

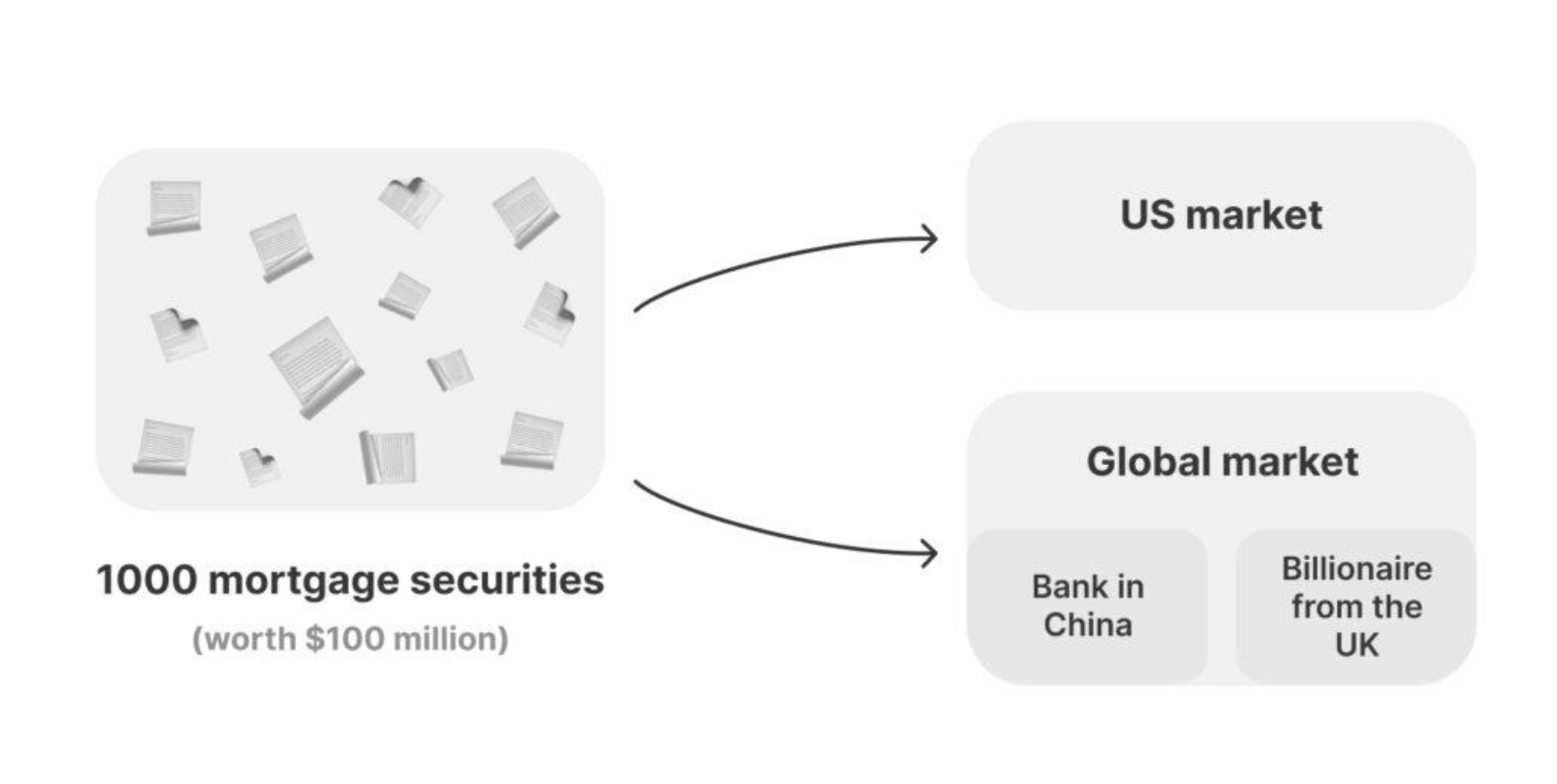

All this created a situation where mortgage securities were bought by pension funds, sovereign funds of national states, and also by private investors who did not want to take risks and weren’t content with a deposit at the inflation rate. In addition, high ratings from rating agencies gave buyers a false sense of security and a false sense of the risk for such an investment. It seemed to investors that, whatever the situation with mortgage loans, everything would be fine. But in fact, even then it was worth thinking about breaking the ties between borrowers and lenders.

Things only got worse

As the government regulated the mortgage industry less and less, the mortgage market gradually changed. But the attitude towards mortgage securities remained the same. Everyone continued to think they were terribly reliable.

Some genius came up with the idea to further confuse the already-complex mortgage scheme by starting to use a new instrument for mortgage securities — the so-called collateralized debt obligations (CDO), by which investment banks or funds combine debts into a single package. In essence, this was a package of bonds insured by something real.

Let’s look at the situation, taking as an example a hypothetical US citizen, who we’ll call Kurt. Kurt is the perfect man. He has a net salary, pays his mortgage on time, and even runs in the mornings. And if Kurt is fired, he has additional earnings and a safety cushion.

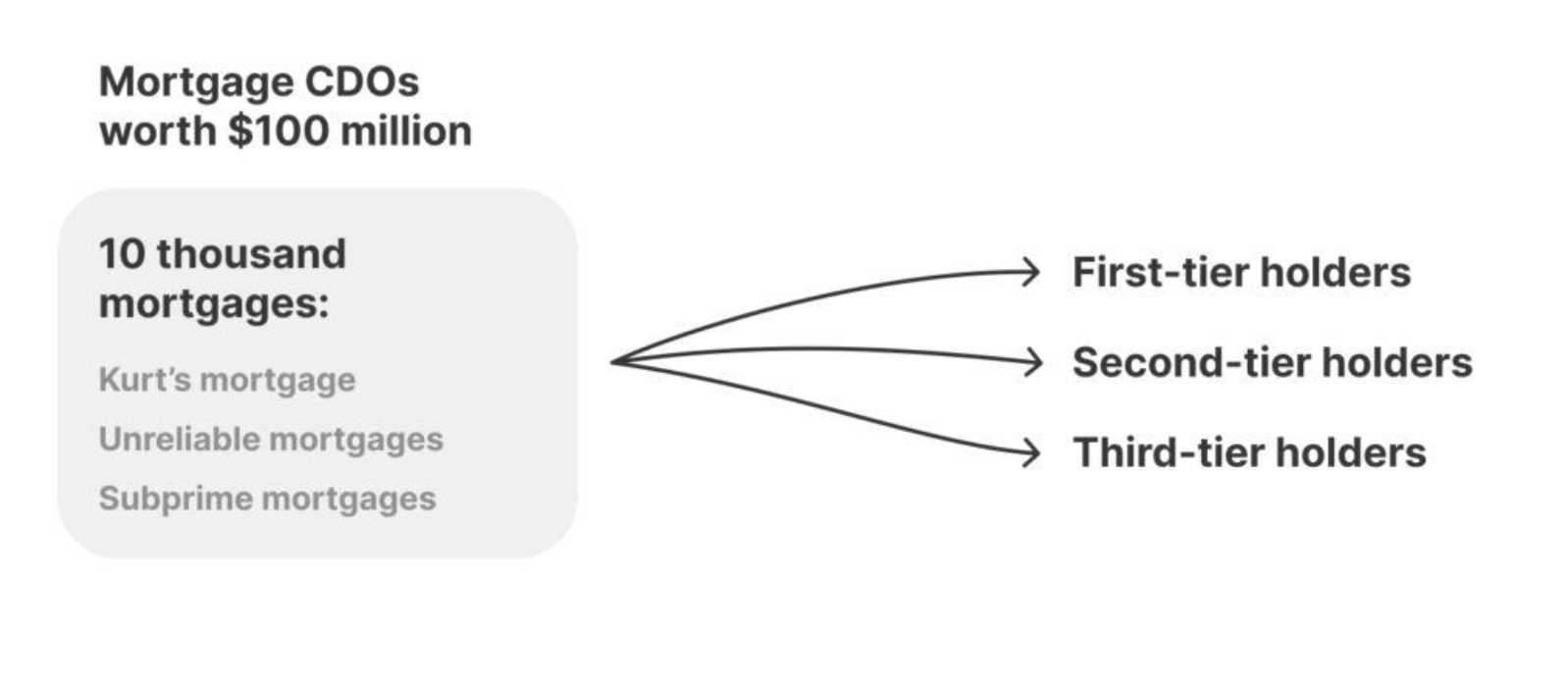

But not everyone in America in those days was like Kurt. Some were too dependent on their low-paid jobs and had no additional income. Many didn’t even have a stable job, and had a subprime mortgage with no clue how they would pay it when the rate rose. And the bankers combined maybe ten thousand individual borrowers with different rates, conditions and reliability levels into a package of mortgage CDOs that they could sell according to the old scheme for maybe $100 million.

Within the CDO, there were multilevel payments, which were distributed between holders.

Those CDOs were not at all reliable. But skillful bankers insured the papers for the same $100 million, so if anything happened, the insurance company would return all the money to the investor. In addition, bankers could pay the rating agency to get a super-reliable rating for their securities, so that by 2002, there were not only reliable mortgage securities with a conditional 4% yield on the market, but also CDOs with a yield of 6% to 15%.

Mortgage-related CDSs, or credit default swaps, were also growing at a similar rate. These were essentially the same insurance, only traded on the stock market. The meaning of the transaction was simple — payments were made not to the insurance company, but to the borrower, but in case of an insured event (for example, non-payment of the mortgage), the borrower would also have to pay. The market for these swaps was revolutionary for the time. It grew insanely, until it finally burst, triggering the crisis. The trouble was that the state, in principle, was not regulating this market. Everything was based on the assumption that the interest on mortgages would continue to be paid, so that insurance would not be required, and there would be no need to pay credit default swaps. A convenient scheme, but as we all know, it did not work.

But this is not the end

Synthetic CDOs were the real harbinger of disaster. Though, in essence, they contained the same mortgage securities, they were not based on the varying degrees of risk and income of those securities, but on insurances on these mortgage securities.

The financial market, in the absence of barriers from the state, began to go crazy. Irresponsible behavior abounded. Enormous bonuses were paid for each security sold by investors. And when, in the midst of the 2008 crisis, when the economy was already in ruins, governments around the world began to prohibit the payment of bonuses to bankers, top banks acted first and paid their executives millions of dollars in bonuses before such laws came into effect.

Again, what happened?

Kurt bought his house on loan and this is his real deal and real house. You made a bet with your neighbour whether Kurt would repay his debt, and then other people made a bet about whether you would win the bet. And a smart banker passing by offered to buy out the bet and sold it to a distant investor on another part of the planet. Obligations began to be bought up and resold.

It seems that all this is already enough for a large-scale crisis. We have an obvious series of inaction, blurring of responsibility, turning a blind eye to problems, and so on. But at that time, no one thought so, and the matter was aggravated by the fact that banks had so-called leverage — the ability to borrow money for their investments on a 12/1 scale. That is, if you had a dollar, then you could borrow another 12 dollars from other banks, organisations or individuals, and invest your money in stocks, securities, CDOs or credit swaps.

But this was not enough for the banks. In 2004, the five largest US investment banks convinced the US government that they didn’t have enough room to work, that they were so large that nothing would happen if their leverage was changed, for example, to a 40/1 scale. To understand what this means, imagine that you told the bank that you had an apartment worth $1 million and suggested the bank give you a loan for $40 million against the security of that apartment. What would any bank on the planet tell you? That you’re crazy! And you’d receive, at best, maybe $900 thousand on the security of your million-dollar apartment. However, the Securities and Exchange Commission, a special agency of the US government, agreed with the banks and allowed them to borrow at 40/1.

Back to the crisis

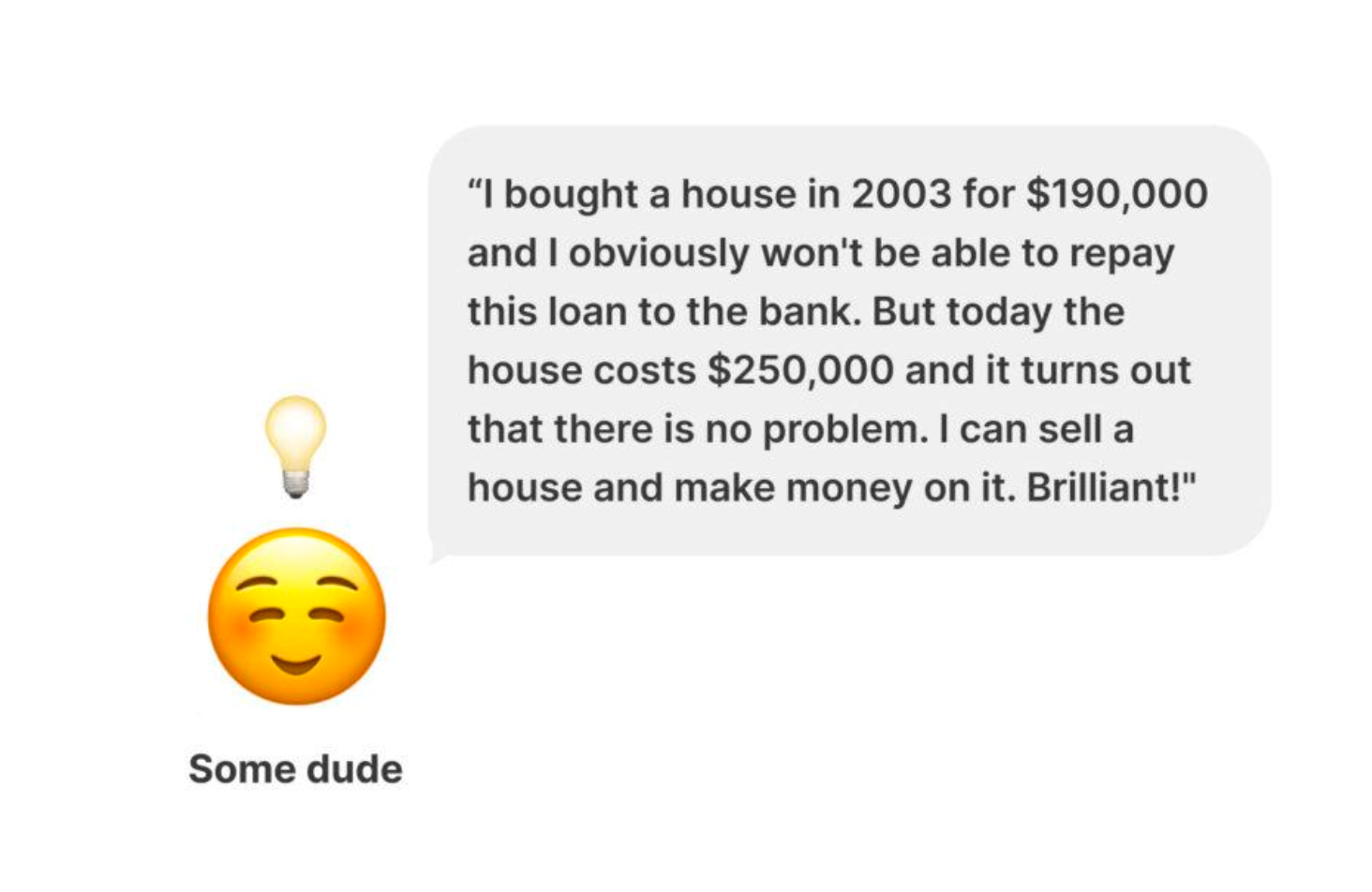

Now let’s get back to 2007, where housing prices are rising at a cosmic speed, and mortgages are issued to just about anyone who wants one. Banks seem not to care whom to give a loan to — the main thing is to give it quickly. And the US market is virtually drowning in money from all over the world. Everyone wants to buy American mortgage debt — so profitable, and so, apparently incredibly secure.

What did this mean for US citizens?

Remember Kurt? He was still paying his mortgages as usual. But those who had taken on a subprime mortgage, buying into the “get your mortgage now, pay later” ad, were in trouble. Many who were already struggling to pay even 2%, were now finding their rate soaring to 10%.

Many decided to put their houses up for sale. But houses that cost $250,000 a couple of months earlier couldn’t fetch even $200,000 now. Just two months had passed, and already those with subprime mortgages had given up and sent a so-called jingle mail to the bank — an envelope containing a letter of insolvency and the keys to the house.

The banks put houses up for auction at knock-down prices. Other homeowners, seeing all of this, began to realize that their own houses might also be worth less than they had thought. Consumer loans that they had taken out on the security of their houses were becoming unbearable burdens. Houses being sold were getting cheaper by the day. This is how the real estate collapse began. But this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Rating agencies woke up and urgently downgraded the CDO reliability rating, meaning that, most likely, the obligations on them would not be honoured. The main problem withCDOs became apparent — since they contained both good mortgages for stable families with a proven income, and mortgages for people who otherwise would never have received a loan, the real price of CDOs was difficult to calculate, making them toxic assets that everyone was trying to get rid of, even at a loss.

At the same time, credit swaps were being sold, as the high risk of mortgages not being paid became clear, meaning that insurance would have to be paid. The price of synthetic CDOs falls to zero.

What about the banks?

Banks and investment funds were in bags of trouble. One of the main problems was that, although they had sold most of the CDOs to investors, they had still kept part for themselves. In addition, you may remember how they had lobbied for the opportunity to borrow more money. The leverage they had got with let’s say $1 billion was now killing them.

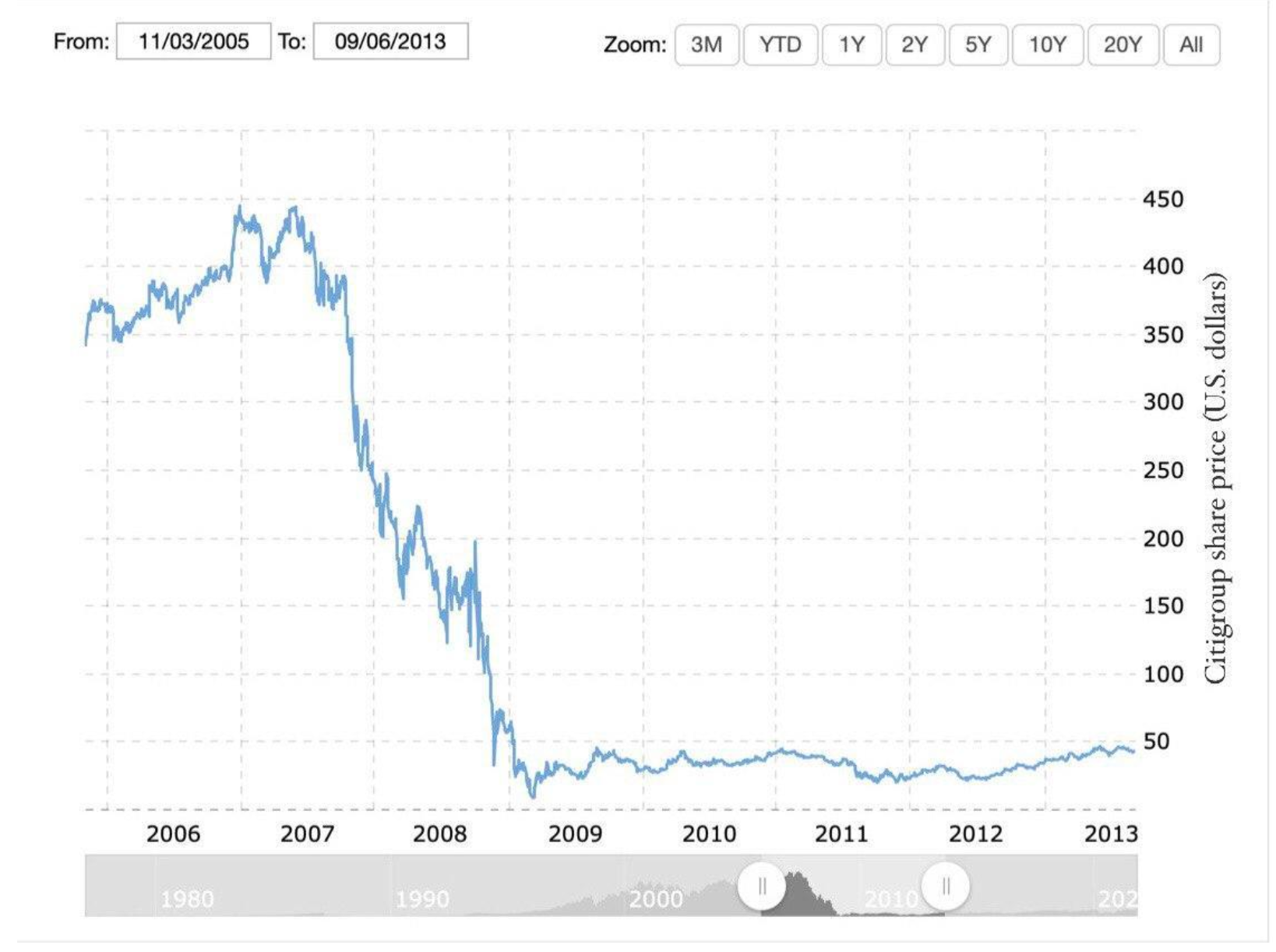

A wave of bankruptcies hit the largest banks in the United States and the world, as bank shares collapsed. For example, in the spring of 2007, Citigroup shares were bought and sold at $443, but by the beginning of 2009, one share cost just $10.

The great American bank Lehman Brothers, which had existed since 1850, survived the American Civil War, both World Wars and the Great Depression, declared itself bankrupt in 2008.

The collapse spread from the banking and financial systems to the stock market. The stocks of countless companies, no matter what their business, collapsed, though not as disastrously as the stocks of banks and investment funds.

A global recession took hold, becoming known as ”The Great Recession” by analogy with The Great Depression. Banks were no longer giving loans. Investors were not investing. Citizens were not buying houses and had cut down enormously on their spending. Many companies sold fewer goods and services, while others could take out new loans to cover old debts and had no option but to declare bankruptcy. Poverty and unemployment grew, and the economy shrank.

The same thing happened worldwide, because companies from all over the world invested in the US. And because of the decline in consumption, world trade also declined. In the absence of government regulation, the banking financial system ate itself up. It looks like a script for a horror movie, doesn’t it?

Holding out for a hero

In the wreckage of the economy and in the midst of the crisis, the US government and Congress began to develop plans to stop the disaster. Some US congressmen suggested letting the banks go bankrupt, but the government decided they were too big to fail, as that would worsen the crisis for decades to come. Some leading economists agreed with them, at least in part, and it was decided to save the banks.

The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act 2008 was passed to legalise the bank bailout program. Remember the problem with the CDOs, the mortgage package that included good and bad borrowers? These were now insanely cheap and so undermined the bank balance. The US government, through the Treasury Department, began to buy these assets from banks and to insure them instead of insurance companies — with taxpayers’ money, of course.

But that was not enough. The banks did not have the money to issue new loans and service old ones. Banks began to issue new shares, and the government began to buy them — thus becoming the owner of the banks. The money went not only to buy back assets and rescue banks. It also went to loans for industry, and another part to support those who could no longer pay their mortgages and risked being left without a home.

The US government worked quite professionally. The market lacked confidence, and no one wanted to issue loans for investment. The government promised to allocate $700 billion for the plan to rescue the banking system, but in the end, they spent about $450 billion. And every dollar spent returned to the US budget by 2014, with even a small profit in the region of half a cent per dollar.

It was important to show business and citizens that everything was in order and that the government was taking the blow, the risks and the responsibility. Not to mention that the entire planned allocation was not even needed. Bank shares, which had been bought by the government, were also sold years later, as were the mortgage securities that they bought. Not all of them were irrevocable. All these urgent measures helped to stabilise the market, and by the end of 2008, a change in government was on the horizon in the United States.

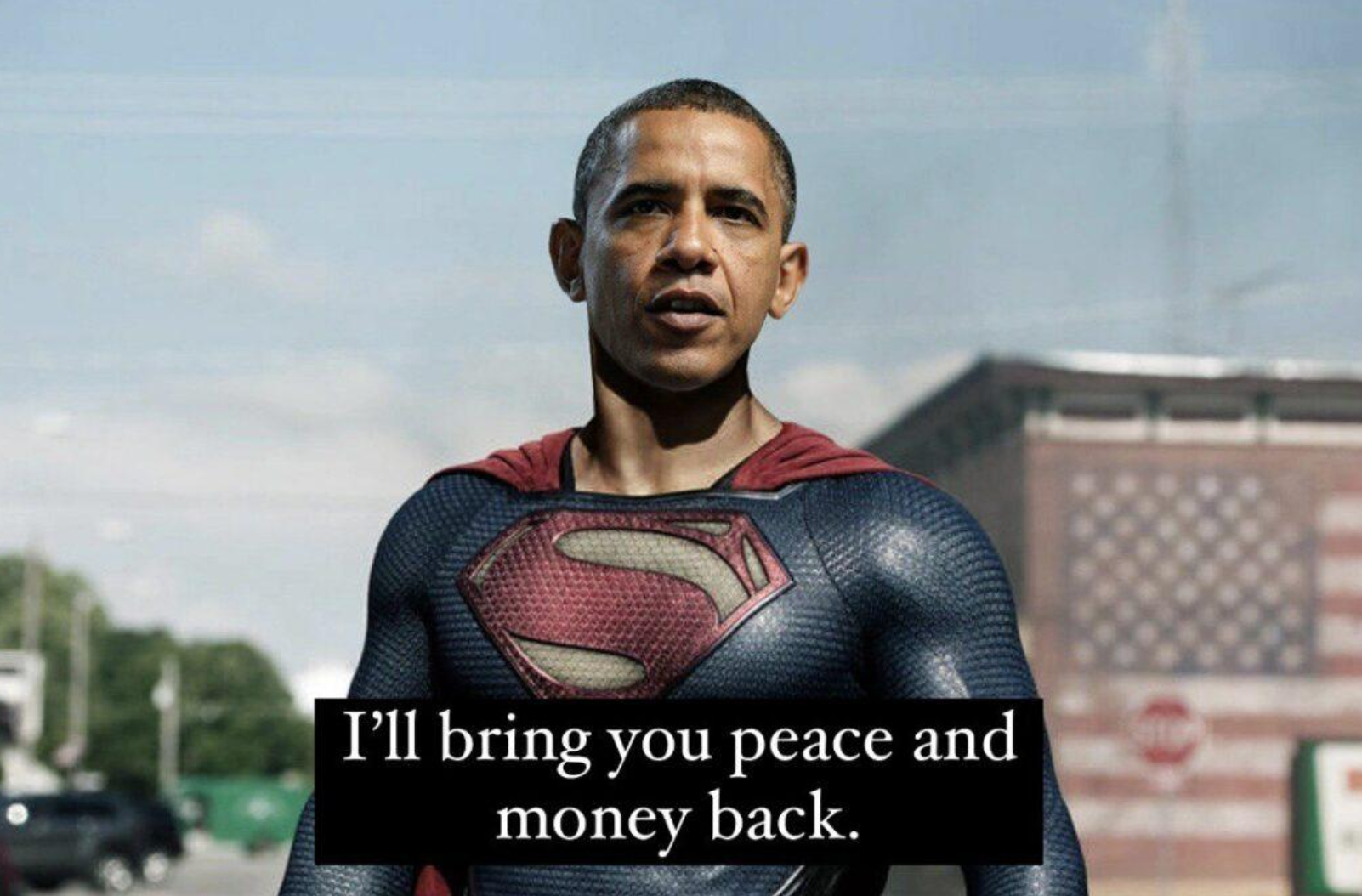

Barack Obama was elected president. His administration did everything possible to save the country from disaster. It delivered a package of various benefits and subsidies for citizens and businesses, which were intended to start operating in 2009 and return the economy to growth again. The first thing the new government did was to cut taxes for citizens, announcing in advance that taxes would return to normal levels by 2011. But for those two years, things became easier for people. Taxes were reduced by $400 for individuals and by $800 for families. Citizens again began to spend money, pay for services and goods, and businesses began to recover.

In addition, Obama’s plan included spending on infrastructure, renewable energy, healthcare and industry. All of this spending was intended to stimulate different sectors of the US economy. It did create a hole in the US budget, but it has fully paid off.

The economy continued to contract, but the following year, 2010, growth returned. The world had gone through not just another economic crisis, but the largest crisis in almost 80 years, since the Great Depression. Capitalism, the market economy, and smart government actions were able to put everything back in place. An unprecedented decade of economic growth followed, which has only now been stopped by a global pandemic.