The Little Book of Safe Money by Jason Zweig

Welcome to the Value Sense Blog, your resource for insights on the stock market! At Value Sense, we focus on intrinsic value tools and offer stock ideas with undervalued companies. Dive into our research products and learn more about our unique approach at valuesense.io

Explore diverse stock ideas covering technology, healthcare, and commodities sectors. Our insights are crafted to help investors spot opportunities in undervalued growth stocks, enhancing potential returns. Visit us to see evaluations and in-depth market research.

Book Overview

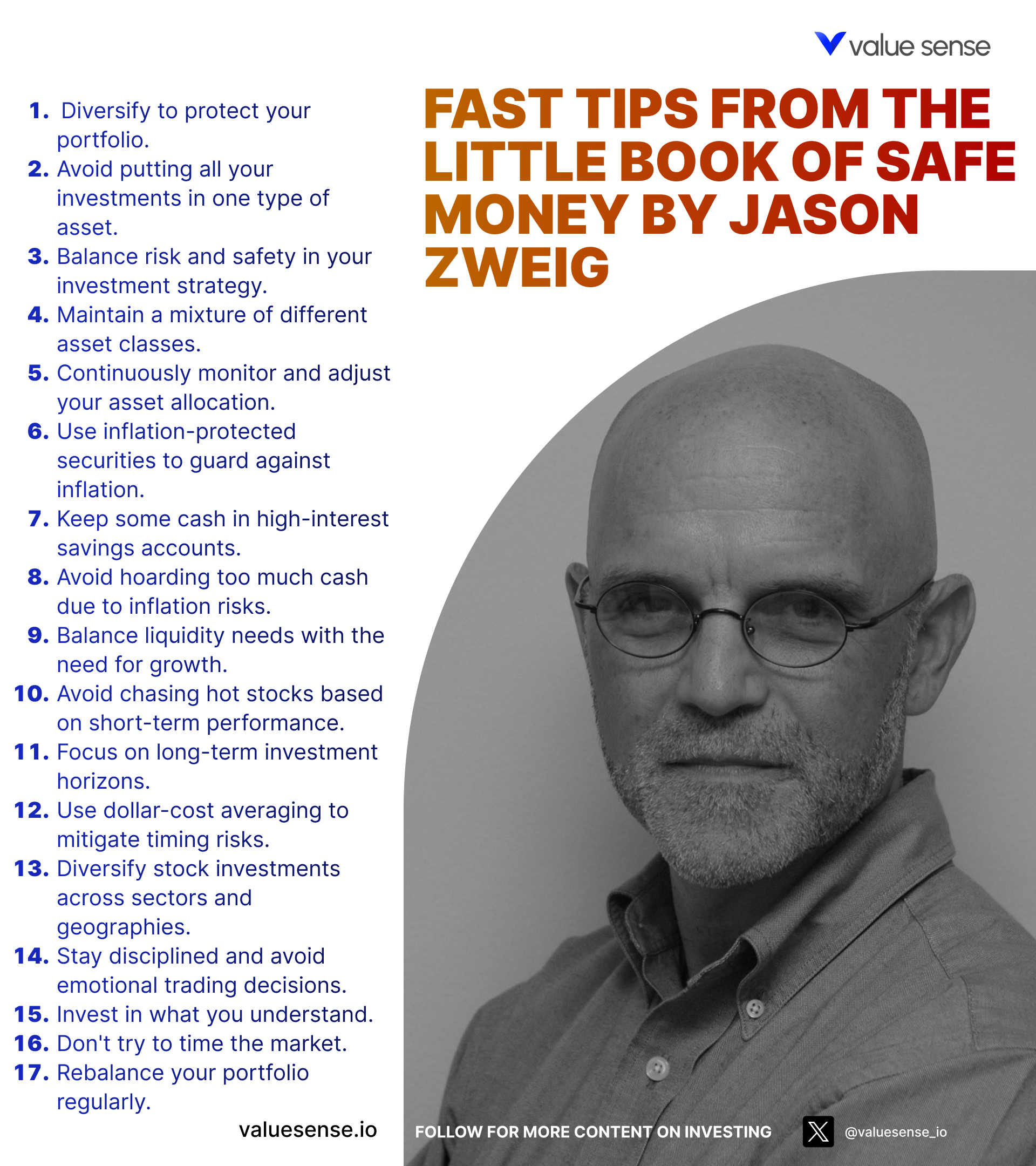

Jason Zweig’s The Little Book of Safe Money stands out as a practical, no-nonsense guide for investors who want to protect and grow their wealth without falling prey to the market’s countless traps. Zweig, a renowned financial journalist and longtime columnist for The Wall Street Journal, brings decades of experience to this book. He is also well-known for his annotated edition of Benjamin Graham’s classic, The Intelligent Investor, and his ability to distill complex financial concepts into actionable advice for everyday investors. Zweig’s credibility is rooted in his deep understanding of behavioral finance and his commitment to investor education, making him a trusted voice in the investment community.

The central theme of The Little Book of Safe Money is caution: Zweig’s philosophy is that safety and prudence should be the foundation of every investment strategy. The book takes readers through the psychological, structural, and practical pitfalls that can erode wealth, especially during market bubbles and panics. Zweig’s purpose is to arm readers with the tools and mindset needed to avoid common traps—be they emotional, structural, or product-based—and to build a portfolio that can withstand shocks and uncertainty. He addresses not just what to invest in, but how to think and behave as a disciplined investor, frequently reminding readers that “the single best way to lose money is to try to get rich quick.”

This book is an essential read for anyone who wants to understand the true meaning of “safe money.” It is particularly valuable for conservative investors, retirees, or anyone who has been burned by market volatility and is seeking a more stable approach. However, its lessons are just as relevant for young professionals, DIY investors, and even experienced market participants who may have grown overconfident in bull markets. Zweig’s writing is accessible, witty, and filled with real-world examples, making it suitable for both beginners and seasoned investors looking to reinforce their discipline.

What sets this book apart is its blend of behavioral insights, practical rules, and myth-busting. Zweig goes beyond the standard advice of diversification and asset allocation, delving into the psychological traps that lead investors astray. He tackles everything from the dangers of “guaranteed” products and leveraged ETFs to the subtle erosions caused by fees and taxes. The book is structured as a series of concise, focused chapters, each addressing a specific aspect of safe investing, with actionable takeaways and memorable anecdotes. Zweig’s use of metaphors—such as comparing investors to eggs or likening spicy food to hot returns—makes the lessons stick and helps readers internalize complex concepts.

Ultimately, The Little Book of Safe Money is a comprehensive manual for those who want to safeguard their financial future. It teaches readers not only how to avoid losing money, but also how to develop the patience, skepticism, and self-awareness required to succeed in investing over the long term. The book’s unique combination of psychological wisdom, practical strategies, and market history makes it a valuable addition to any investor’s library.

Key Concepts and Ideas

Zweig’s investment philosophy is rooted in the principle that capital preservation should always come before the pursuit of extraordinary returns. He believes that most investors are far more vulnerable to psychological traps and market hype than they realize, and that the best way to build wealth is through patience, discipline, and skepticism. Zweig’s approach to safe money isn’t about avoiding risk altogether, but about understanding, managing, and respecting it. He warns that the financial industry is designed to exploit impatience and greed, and that investors must cultivate a mindset of humility and caution to avoid costly mistakes.

The book’s central ideas revolve around the need to avoid unnecessary risks, the importance of liquidity, the dangers of behavioral biases, and the perils of complex or “guaranteed” products. Zweig emphasizes that true safety comes not from chasing the latest fads or relying on seemingly foolproof products, but from building a well-diversified, transparent, and low-cost portfolio. He also highlights the importance of understanding one’s own human capital, the impact of fees and taxes, and the psychological warfare that investors face from both the markets and the financial industry itself.

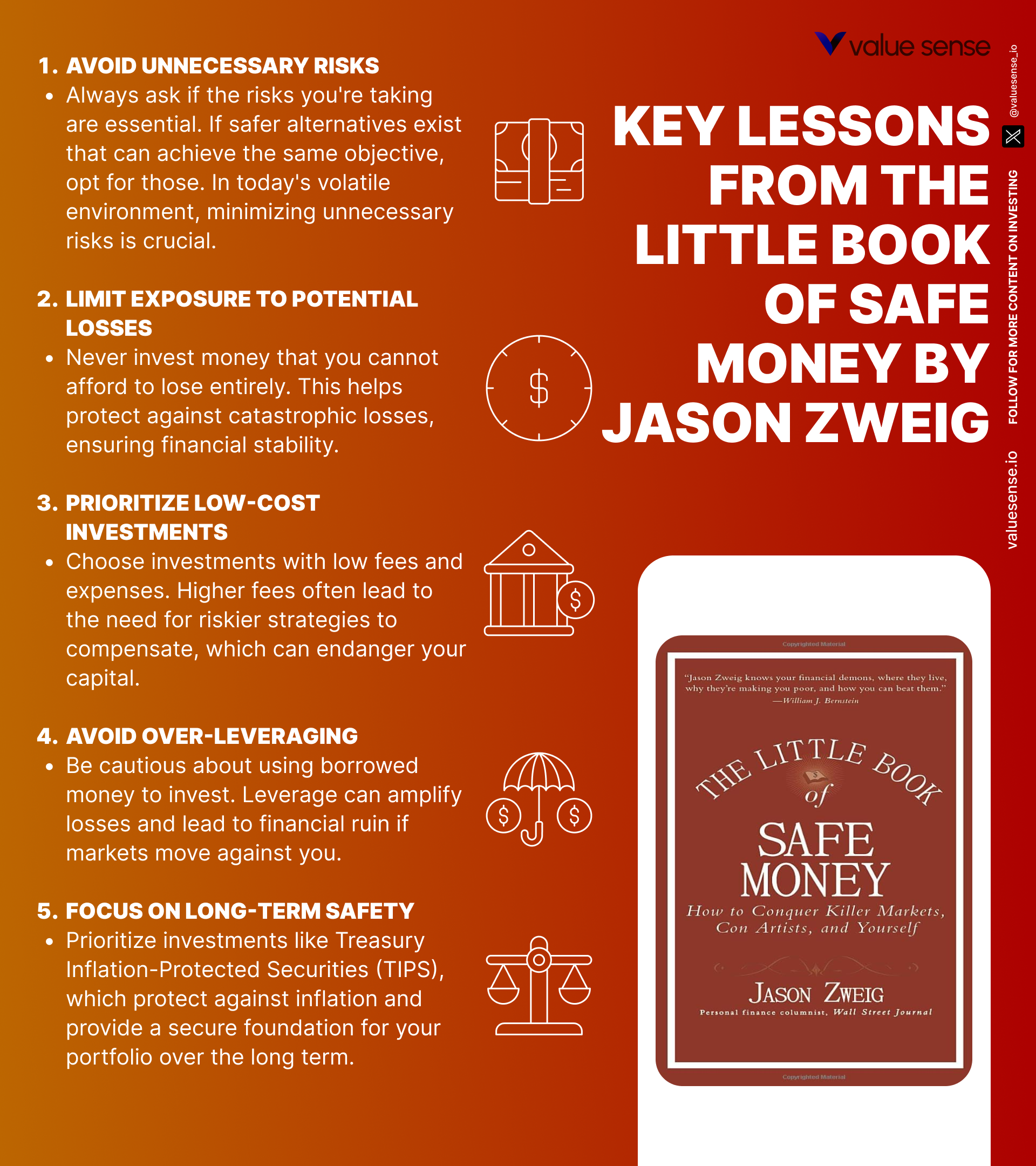

- The Three Commandments of Safe Investing: Zweig opens the book with three essential rules—avoid unnecessary risk, only take risks likely to be rewarded, and never risk more than you can afford to lose. These commandments form the backbone of the entire book, guiding readers to question every investment decision with these criteria in mind.

- Liquidity and Solidity: The book stresses the importance of keeping a portion of your portfolio in assets that are both solid (retain value) and liquid (easy to sell). Zweig warns that in times of crisis, assets that seem liquid can quickly become illiquid, leading to forced sales at distressed prices.

- Human Capital as Your Biggest Asset: Zweig introduces the concept of human capital—the present value of your future earnings—as the core of your financial life. He advises against concentrating investments in your own industry and recommends diversifying to protect both your job and your investments.

- The Dangers of Guarantees: The book debunks the myth that investment guarantees are foolproof, explaining that most guarantees come with loopholes, exclusions, or hidden costs. Zweig urges skepticism and a preference for diversification over reliance on guarantees.

- The Illusion of Safety in Yield Chasing: Zweig cautions against chasing higher yields in cash or fixed-income products, warning that seemingly “safe” high-yield investments often carry hidden risks that can lead to losses.

- Behavioral Biases and Emotional Traps: The book explores how emotions like greed, fear, and overconfidence can sabotage investment decisions. Zweig provides tools for recognizing and controlling these biases, such as setting clear goals and practicing mindfulness.

- The Perils of Complexity and Acronyms: Zweig warns that products with catchy acronyms (like CDOs, ETFs, etc.) are often more complex and risky than they appear. He advises investors to favor simplicity and full understanding over complexity and marketing hype.

- Cost Vigilance: Fees and Taxes: Even small fees and taxes can erode returns over time. Zweig advocates for low-cost investing, tax-efficiency, and attention to detail in all aspects of portfolio management.

- Critical Thinking and Skepticism: The book encourages investors to question all advice, market commentary, and financial news. Zweig insists that skepticism and evidence-based decision-making are essential for survival in the markets.

- Long-Term Discipline and Patience: Above all, Zweig preaches the virtues of patience, long-term focus, and resisting the urge to act on short-term impulses. He reminds readers that wealth is built over decades, not days.

Practical Strategies for Investors

Zweig’s book is filled with actionable strategies that investors can implement immediately to make their portfolios safer and more resilient. His advice is grounded in real-world market history, psychological research, and decades of observing both the successes and failures of ordinary investors. The strategies outlined in the book are designed to help investors avoid catastrophic losses, minimize the impact of behavioral mistakes, and maximize the compounding of wealth over time.

Applying Zweig’s teachings begins with a shift in mindset: investors must accept that there are no shortcuts to wealth and that the pursuit of “hot” returns is a recipe for disaster. Instead, the focus should be on building a portfolio that can weather market storms, provide liquidity when needed, and grow steadily over the long run. Zweig’s strategies are especially relevant in today’s environment, where market volatility, product complexity, and marketing hype are at all-time highs.

- Build a Liquidity Buffer: Always keep a portion of your portfolio in highly liquid, safe assets such as Treasury bills or high-yield savings accounts. This buffer allows you to cover emergencies or take advantage of opportunities without being forced to sell long-term investments at a loss.

- Diversify Beyond Your Career: Avoid concentrating your investments in your own industry or company. If you work in tech, invest in healthcare, consumer staples, or bonds to hedge against sector-specific downturns that could affect both your job and your investments.

- Reject Yield Chasing: Don’t fall for high-yield cash or bond products that promise safety with extra returns. Stick to plain, transparent vehicles like TIPS, short-term Treasuries, or insured bank accounts for your cash reserves.

- Scrutinize Guarantees: Before investing in any product with a “guarantee,” read the fine print and understand the exclusions, limitations, and costs. Prefer well-diversified portfolios over products that rely on guarantees for safety.

- Focus on Low-Cost Investing: Use index funds and ETFs with rock-bottom expense ratios. Even a 1% annual fee can reduce your nest egg by tens of thousands over decades. Reinvest dividends and use tax-advantaged accounts to maximize compounding.

- Set Clear, Long-Term Goals: Write down your financial goals and investment plan. Review and update them regularly to stay focused and prevent emotional decisions during market turbulence.

- Practice Mindful Investing: Limit your exposure to financial news and market noise. Make decisions based on your plan, not headlines or hype. Use stop-loss orders or automatic rebalancing to enforce discipline.

- Question All Advice and Products: Always ask “Who benefits?” when receiving investment advice or being pitched a new product. Seek evidence-based, unbiased guidance and avoid products you don’t fully understand.

Most investors waste time on the wrong metrics. We've spent 10,000+ hours perfecting our value investing engine to find what actually matters.

Want to see what we'll uncover next - before everyone else does?

Find Hidden Gems First!

Chapter-by-Chapter Insights

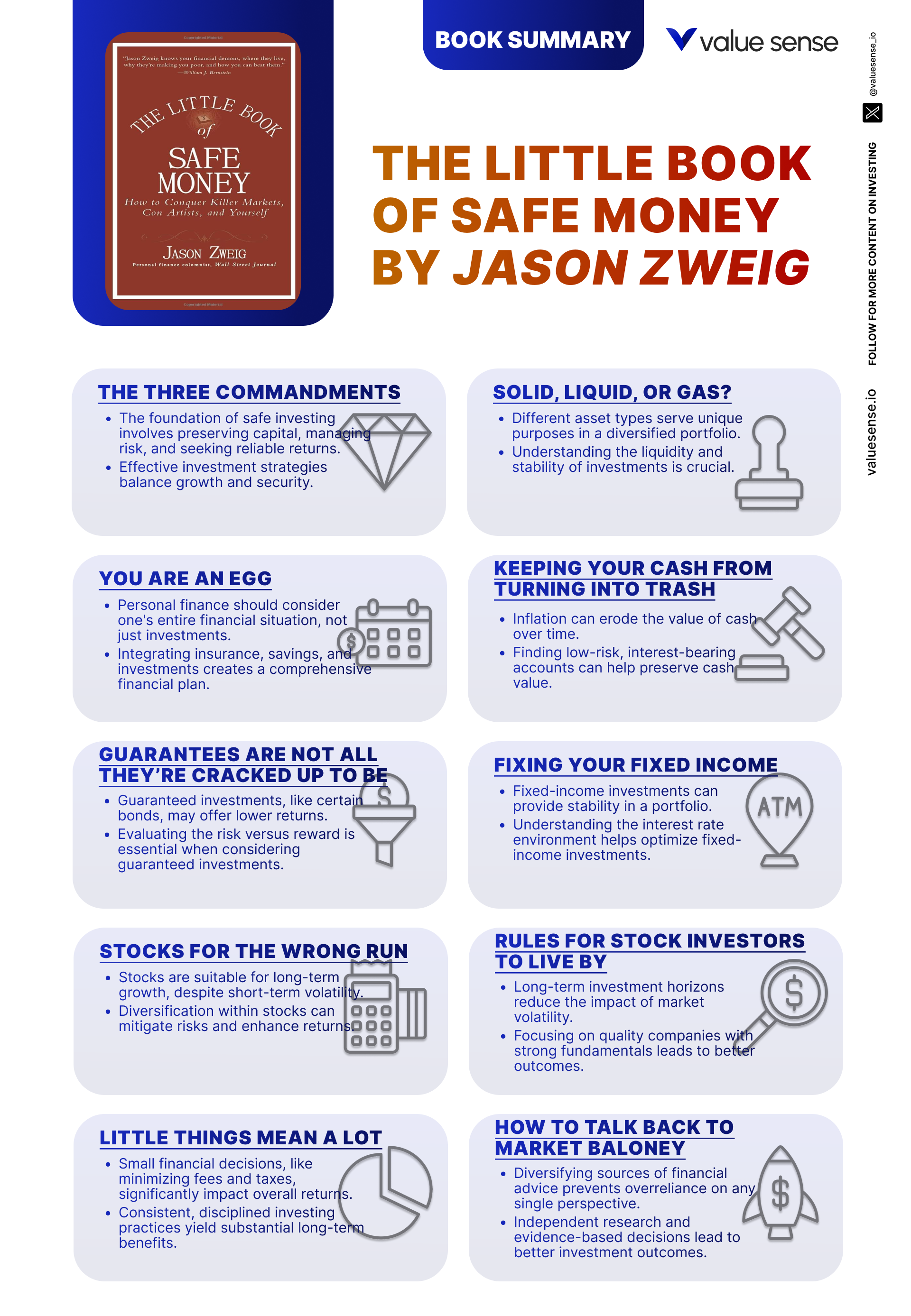

Zweig structures The Little Book of Safe Money as a series of concise, focused chapters, each tackling a distinct aspect of safe investing. The progression of chapters takes readers from foundational principles to specific asset classes, psychological traps, and the pitfalls of modern financial products. Each chapter is packed with memorable metaphors, real-world case studies, and practical tools for investors at every level. This structure makes the book easy to digest, while ensuring that every critical topic is addressed in depth.

The book begins with the core commandments of safe investing, then explores the practicalities of liquidity, human capital, and the role of cash. It then systematically debunks common myths about guarantees, bonds, stocks, and alternative investments like hedge funds and commodities. Later chapters delve into the psychological and behavioral challenges investors face, before concluding with advice on navigating market hype and bad advice. Below, you’ll find a detailed, chapter-by-chapter analysis, with each section highlighting the main ideas, specific examples and data, practical applications, and historical or contemporary context.

Chapter 1: The Three Commandments

The opening chapter sets the tone for the book by introducing Zweig’s “Three Commandments” of safe investing: avoid unnecessary risk, only take risks likely to be rewarded, and never risk more than you can afford to lose. Zweig illustrates these principles with anecdotes of investors who lost fortunes by ignoring them, such as retirees who chased high-yield bonds in 2008 only to see their savings evaporate. He stresses that every investment decision should start with the question: “Is there a safer way to achieve this goal?” This mindset is the foundation for all subsequent advice in the book.

To reinforce these commandments, Zweig provides specific examples from recent financial crises. He references the collapse of supposedly “safe” mortgage-backed securities in 2007-2008, which were rated AAA but carried hidden risks that wiped out investors who thought they were immune to loss. He also cites data showing that even “blue chip” stocks can lose more than half their value in bear markets, underscoring the need for humility and caution. Zweig writes, “The single best way to lose money is to try to get rich quick,” reminding readers that risk is omnipresent, even in seemingly safe investments.

Investors can apply these commandments by conducting a “worst-case scenario” analysis before making any investment. Zweig suggests asking: “If this investment goes south, can I recover? Will my lifestyle be disrupted?” He recommends keeping risky assets within strict limits and always having a plan for how to respond if things go wrong. This approach is especially relevant for retirees or those nearing retirement, who cannot afford large drawdowns late in life.

Historically, investors who followed these rules—such as Warren Buffett, who famously avoids leverage and only invests in businesses he understands—have weathered crises far better than those who ignored them. In the aftermath of the dot-com bust and the 2008 meltdown, those who stuck to the Three Commandments preserved their capital and were able to buy bargains when others were forced to sell. Zweig’s timeless advice remains crucial in today’s volatile markets, where new “safe” products and fads constantly tempt investors to break these cardinal rules.

Chapter 2: Solid, Liquid, or Gas?

In this chapter, Zweig explores the concepts of liquidity and solidity, likening investments to the states of matter. He argues that a sound portfolio should contain assets that are both “solid” (retain value over time) and “liquid” (easy to sell at fair value). Zweig warns that many investors mistake apparent liquidity for real liquidity, only to find in a crisis that their assets are “gaseous”—evaporating when most needed. He uses the 2008 financial crisis as a case study, when even money market funds and corporate bonds became difficult to sell without steep losses.

Specific examples abound: Zweig describes how auction-rate securities, once marketed as “cash equivalents,” froze in 2008, leaving investors unable to access their savings. He notes that real estate, while seemingly solid, can become highly illiquid in downturns, with properties languishing on the market for months or years. Data from the crisis shows that many investors were forced to sell stocks or mutual funds at fire-sale prices to raise cash, compounding their losses.

To apply these lessons, Zweig recommends maintaining a liquidity buffer—at least six months’ worth of living expenses in true cash or near-cash instruments. He suggests regularly reviewing your portfolio’s liquidity profile and stress-testing it for crisis scenarios. Avoid overleveraging or borrowing against investments, as margin calls can force sales at the worst possible times. For those with illiquid assets like real estate or private equity, Zweig advises keeping an even larger cash reserve.

The chapter’s historical context is clear: during every major market panic—from the 1987 crash to the COVID-19 selloff in 2020—liquidity has dried up exactly when investors needed it most. Zweig’s advice echoes the lessons learned by legendary investors like John Templeton and Ray Dalio, who always kept a portion of their portfolios in cash or ultra-liquid assets. In today’s world of ETFs and algorithmic trading, where liquidity can vanish in minutes, this lesson is more important than ever.

Chapter 3: You Are an Egg

This chapter introduces the idea of “human capital”—the present value of your future earnings—as your most important asset. Zweig argues that most investors underestimate the risk of concentrating both their job and their investments in the same industry. He uses the metaphor of an egg: if you put all your eggs in one basket (your career and your investments), a downturn in your industry could break them all at once. Zweig cites examples of Enron employees who lost both their jobs and their retirement savings when the company collapsed.

He provides data showing that workers in cyclical industries (like energy, tech, or construction) are especially vulnerable. During the 2001 tech bust, Silicon Valley professionals who held both stock options and mutual funds focused on technology suffered devastating losses. Zweig recommends diversifying your portfolio away from your own industry and using products like Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) to hedge against inflation risk, particularly if your salary is not inflation-adjusted.

Practically, investors should start by mapping out their human capital and identifying risks specific to their profession. For example, a healthcare worker might invest more in technology or consumer staples, while a tech worker should avoid overweighting tech stocks. Zweig also encourages using insurance products—like disability or unemployment insurance—to further protect your human capital. TIPS and other inflation-hedged assets can safeguard your purchasing power if your income is sensitive to rising costs.

Historically, the collapse of companies like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns illustrates the dangers of concentrated risk. Employees who invested heavily in company stock lost both their jobs and their retirement funds in one blow. Zweig’s advice is especially relevant in the age of stock-based compensation and gig work, where income streams can be unpredictable. By treating human capital as an asset to be protected and diversified, investors can build much more resilient financial lives.

Chapter 4: Keeping Your Cash from Turning into Trash

Zweig tackles the role of cash in a portfolio, debunking myths about high-yield cash products and the dangers of chasing returns in what should be the safest part of your investment plan. He recounts how, during the 2008 crisis, investors stampeded into Treasury bills at negative real yields—guaranteeing small losses just to feel safe. He warns that products promising “safe” high yields, like auction-rate securities or certain money market funds, often carry hidden risks that can result in loss of principal or liquidity.

He provides examples of cash equivalents that failed during crises, such as Reserve Primary Fund, which “broke the buck” in 2008 and triggered a run on money market funds. Zweig also discusses the dangers of “teaser” rates on bank accounts or CDs, which lure investors with high initial yields that quickly drop. Data shows that, over time, the highest-yielding cash products often underperform due to fees, restrictions, or default risk.

For practical application, Zweig recommends matching the time horizon of your cash needs to the maturity of your cash investments. For money needed in the next year, stick to insured savings accounts, short-term Treasuries, or government money market funds. For longer-term reserves, consider TIPS or laddered CDs. Never chase yield in the cash portion of your portfolio, and always prioritize liquidity and safety over returns.

Historically, the lesson is clear: in every crisis, investors who chased yield in supposedly safe products—like mortgage-backed securities in 2007 or European bank deposits during the Euro crisis—have suffered unexpected losses. Zweig’s advice is to treat cash as an insurance policy, not an investment. In today’s low-interest-rate world, this discipline is more important than ever, as the temptation to reach for yield remains high.

Chapter 5: Guarantees Are Not All They’re Cracked Up to Be

This chapter explores the seductive appeal of investment guarantees, from principal-protected notes to annuities and insurance products. Zweig warns that most guarantees are riddled with fine print, exclusions, and loopholes that limit their effectiveness. He cites examples of “guaranteed” products that failed to deliver in market downturns, such as variable annuities with withdrawal guarantees that were suspended or restructured after 2008.

Zweig provides data on the costs of guarantees, showing that products with guarantees often charge high fees—sometimes 2-3% per year—eroding potential returns. He also explains that guarantees are only as good as the issuer’s ability to pay; during the financial crisis, even insurance companies faced solvency issues, putting guarantees at risk. The chapter includes anecdotes of investors who misunderstood the limitations of their products and were left with losses when they needed protection most.

Investors can apply this lesson by reading the fine print of any guaranteed product, asking tough questions about exclusions, and comparing the costs to the benefits. Zweig recommends favoring diversification and transparency over complicated guarantees, and using simple, low-cost products for most of your portfolio. If you do use guarantees, make sure they are backed by highly rated, financially strong institutions, and limit their share of your assets.

Historically, the collapse of AIG in 2008 and the suspension of “guaranteed” money market funds are cautionary tales. Investors who relied solely on guarantees, without understanding the underlying risks, suffered unexpected losses. Zweig’s skepticism is especially relevant today, as the market is flooded with new “guaranteed” products targeting risk-averse investors. His advice: there are no free lunches, and the best guarantee is a well-diversified, transparent portfolio.

---

Explore More Investment Opportunities

For investors seeking undervalued companies with high fundamental quality, our analytics team provides curated stock lists:

📌 50 Undervalued Stocks (Best) overall value plays for 2025

📌 50 Undervalued Dividend Stocks (For income-focused investors)

📌 50 Undervalued Growth Stocks (High-growth potential with strong fundamentals)

🔍 Check out these stocks on the Value Sense platform for free!

---

Chapter 6: Fixing Your Fixed Income

Zweig demystifies the world of bonds and fixed-income investments, explaining that while bonds are often seen as “safe,” they carry their own set of risks—especially in a rising interest rate environment. He details how long-term bonds can lose significant value when rates rise, citing the example of 30-year Treasury bonds, which lost over 20% in value during the 1994 rate spike. Zweig also discusses inflation risk, which erodes the purchasing power of fixed payments over time.

He provides data showing that, from 1970 to 2020, inflation averaged around 3.8% per year, meaning that a bond yielding 4% barely kept pace with rising costs. Zweig advises diversifying fixed-income holdings across maturities and credit qualities, and warns against reaching for yield in junk bonds or complex structured products. He highlights the advantages of TIPS, which adjust principal for inflation, as a core holding for safety-focused investors.

Practically, Zweig recommends building a bond ladder—spreading investments across different maturities to reduce interest rate risk. He suggests keeping the average duration of your bond portfolio short, especially when rates are expected to rise. For tax-sensitive investors, municipal bonds may offer advantages, but only if they are high quality and truly diversify your risk. Avoid concentrated bets on any single issuer or sector.

The lessons of the 2008 crisis, when even AAA-rated mortgage bonds defaulted, and the 2022-2023 bond bear market, when long-duration Treasuries lost over 30%, reinforce Zweig’s message. Safe fixed income is about stability, not chasing the highest yield. In today’s uncertain world, investors must be especially wary of “safe” products that promise more than they can deliver.

Chapter 7: Stocks for the Wrong Run

In this chapter, Zweig challenges the mantra that “stocks are always best for the long run.” He points out that while stocks have historically outperformed bonds over decades, they can be highly volatile and deliver poor results over shorter periods. Zweig cites data showing that, between 2000 and 2010, the S&P 500 delivered a negative total return, despite being considered a “safe long-term investment.” He warns against overconfidence in stock markets and the dangers of assuming that past performance guarantees future results.

He provides examples of investors who bet heavily on stocks in 2007, only to see their portfolios cut in half during the 2008 crash. Zweig emphasizes the importance of matching your stock allocation to your time horizon and risk tolerance. He recommends diversifying across sectors, industries, and countries to reduce the risk of catastrophic losses from a single market downturn.

For practical application, Zweig suggests using target-date funds or balanced funds to automate diversification and rebalancing. He also advises setting realistic expectations for stock returns—assuming no more than 6-7% annualized over the long term—and being prepared for periods of flat or negative returns. Investors should regularly review their allocations and rebalance to maintain discipline, especially after major market moves.

Historically, the dot-com bust, the 2008 global financial crisis, and the 2020 pandemic selloff all demonstrate that stocks can underperform for years or even decades. Zweig’s advice to temper enthusiasm and maintain diversification is especially relevant in today’s market, where technology stocks have dominated returns but remain vulnerable to sharp corrections. The lesson: stocks are a powerful tool, but only when used with caution and a long-term perspective.

Chapter 8: Rules for Stock Investors to Live By

This chapter distills Zweig’s rules for successful stock investing, focusing on discipline, patience, and risk management. He warns against overtrading and emotional decision-making, citing studies showing that frequent traders underperform buy-and-hold investors by 2-4% per year. Zweig emphasizes the importance of diversification, noting that even the best companies can suffer unexpected setbacks. He recommends spreading investments across at least 15-20 stocks in different industries to minimize the impact of any single failure.

Zweig provides data on the destructive power of fees and taxes, showing that high-turnover strategies not only increase costs but also generate short-term capital gains, eroding after-tax returns. He advises investors to focus on company fundamentals—profits, cash flow, and balance sheet strength—rather than chasing hot tips or momentum. Zweig also recommends setting stop-loss orders or using trailing stops to limit downside risk, especially for volatile positions.

Practically, investors should create a written investment policy statement outlining their goals, risk tolerance, and rules for buying and selling. Zweig suggests using dollar-cost averaging to reduce the impact of market volatility and reviewing portfolios quarterly to ensure alignment with long-term objectives. Avoid margin and leverage, as these amplify both gains and losses and can lead to forced selling in downturns.

Historically, patient, disciplined investors—such as those who held through the 2008 crash and rebalanced into undervalued stocks—have outperformed those who panicked or chased fads. Zweig’s rules echo the practices of legendary investors like Peter Lynch and John Bogle, who built fortunes by sticking to simple, repeatable strategies. In today’s era of meme stocks and algorithmic trading, these timeless principles are more crucial than ever.

Chapter 9: Little Things Mean a Lot

Zweig highlights the outsized impact of seemingly minor factors—fees, taxes, and compounding—on long-term investment success. He presents data showing that a 1% annual fee can reduce a $500,000 portfolio by over $140,000 over 30 years. Zweig also illustrates how tax-efficient investing, such as using IRAs, Roth accounts, and tax-loss harvesting, can add 1-2% to annual returns, compounding into substantial wealth over time.

He provides examples of investors who ignored small costs and ended up with significantly less wealth in retirement. Zweig discusses the importance of reinvesting dividends and starting early, showing that even small, regular contributions can grow into large sums thanks to compound interest. He warns that attention to detail—like choosing the right account type or minimizing trading—can make or break your financial plan.

Practically, Zweig recommends using low-cost index funds and ETFs, automating contributions and dividend reinvestment, and reviewing all account statements for hidden fees. He suggests working with a tax advisor to optimize account structures and take advantage of available deductions or credits. Regular portfolio reviews can catch small leaks before they become major problems.

Historically, the rise of index funds and robo-advisors has made low-cost, tax-efficient investing accessible to all. Zweig’s focus on the “little things” is a reminder that, in investing, small edges compound into big advantages. In an age where many investors chase the next big thing, those who mind the details quietly build lasting wealth.

Chapter 10: How to Get Your Kids through College without Going Broke

This chapter addresses the challenge of saving for college without sacrificing your own financial security. Zweig discusses the skyrocketing costs of higher education, noting that average tuition and fees have risen over 200% since 1990. He warns against prioritizing college savings over retirement, citing data that shows parents who do so often end up financially insecure later in life. Zweig recommends starting early, using tax-advantaged 529 plans, and setting realistic expectations for what you can afford.

He provides examples of families who took on excessive student loan debt, only to struggle for decades with repayment. Zweig explains the pros and cons of student loans, grants, scholarships, and work-study programs, and urges parents to explore all options before borrowing. He also discusses the importance of considering in-state schools or community colleges to reduce costs, and of having honest conversations with children about financial realities.

Practically, Zweig suggests setting up automatic contributions to a 529 plan, investing in age-based portfolios that become more conservative as college approaches, and regularly reviewing progress toward savings goals. He advises against tapping retirement accounts for college expenses, as this can jeopardize your own long-term security. Use net price calculators to estimate real costs and avoid overcommitting to unaffordable schools.

Historically, student loan debt in the U.S. has ballooned past $1.7 trillion, with many families caught in a cycle of borrowing and repayment. Zweig’s advice is a timely corrective, emphasizing that the best gift you can give your children is your own financial stability. In today’s world of rising tuition and uncertain job markets, disciplined, realistic planning is more important than ever.

Chapter 11: What Makes Ultra ETFs Mega-Dangerous

Zweig exposes the hidden dangers of ultra ETFs—leveraged and inverse exchange-traded funds that promise to double or triple the daily returns of an index. He explains that while these products can deliver spectacular short-term gains, they are designed for day traders, not long-term investors. Zweig provides data showing that, due to the compounding effects of daily resets, holding ultra ETFs over weeks or months can result in returns that diverge dramatically from the underlying index—often to the investor’s detriment.

He gives examples from the 2008-2009 market, when many leveraged ETFs lost more than twice the market’s decline, and some even went to zero. Zweig notes that the complexity of these products is often hidden behind marketing hype and catchy acronyms, luring unsophisticated investors into taking risks they don’t understand. He warns that the volatility drag in leveraged ETFs makes them unsuitable for buy-and-hold strategies.

For investors, the takeaway is clear: avoid ultra ETFs unless you fully understand their mechanics and are prepared to monitor them daily. Zweig suggests sticking to plain vanilla index funds or traditional ETFs for core holdings. If you do use leveraged products, keep the position size small and set strict stop-loss orders to limit potential losses.

Historically, the rapid growth of leveraged and inverse ETFs has led to numerous regulatory warnings and investor lawsuits. Zweig’s critique is echoed by the SEC and FINRA, which have repeatedly cautioned that these products are inappropriate for most investors. In an era of meme stocks and social media-driven trading, Zweig’s warnings are more relevant than ever.

Chapter 12: Hedge Fund Hooey

Zweig takes aim at the mystique of hedge funds, arguing that their reputation for superior returns is largely a myth. He provides data showing that, after fees, most hedge funds underperform low-cost index funds over time. Zweig explains the “2 and 20” fee structure—2% management fee and 20% of profits—can eat up most of any outperformance. He cites studies indicating that, from 2000 to 2020, the average hedge fund delivered returns barely above inflation, while charging exorbitant fees and offering little transparency.

He recounts stories of famous hedge funds that blew up, such as Long-Term Capital Management in 1998 and Amaranth Advisors in 2006, losing billions in days due to leverage and complex derivatives. Zweig warns that the lack of transparency and regulatory oversight makes it difficult for investors to assess real risks. He also notes that hedge funds often use strategies that are hard to understand or replicate, making them unsuitable for most individuals.

Practically, Zweig advises steering clear of hedge funds unless you have access to top-tier managers and can tolerate high fees, illiquidity, and potential losses. For most investors, he recommends sticking to diversified, low-cost funds that offer transparency and liquidity. If you are tempted by alternative investments, limit your exposure to a small fraction of your portfolio and demand full disclosure of fees and risks.

Historically, the hedge fund industry has seen periods of boom and bust, with many funds closing after poor performance or scandals. Zweig’s skepticism is shared by many institutional investors, who have shifted billions out of hedge funds in recent years. In today’s environment, where transparency and cost control are paramount, Zweig’s advice remains spot-on.

Chapter 13: Commodity Claptrap

Zweig explores the risks and misconceptions of investing in commodities, such as gold, oil, and agricultural products. He explains that while commodities are often marketed as inflation hedges and diversifiers, they are highly volatile and driven by unpredictable factors like weather, geopolitics, and global demand. Zweig provides data showing that, from 1980 to 2020, broad commodity indexes underperformed both stocks and bonds, with wild swings in value.

He gives examples of commodity busts, such as the collapse in oil prices from $140 to $30 per barrel in 2014-2016, and the 2011-2015 gold crash, when prices fell by over 40%. Zweig warns that most commodity investments require complex instruments like futures contracts, which are difficult for retail investors to manage. He also notes that the costs of trading, storage, and roll yield can erode returns even in rising markets.

For investors, Zweig recommends limiting commodity exposure to a small portion of the portfolio, if at all. He suggests using broad-based funds rather than betting on individual commodities, and focusing on assets like TIPS or real estate for inflation protection. Avoid products with high fees or leverage, and be wary of marketing claims about “crisis-proof” performance.

Historically, commodities have experienced long periods of poor returns, punctuated by brief booms and busts. Zweig’s analysis is supported by academic research showing that, over the long term, commodities add little to portfolio returns while increasing volatility. In today’s uncertain world, Zweig’s cautionary approach is a valuable counterweight to commodity hype.

Chapter 14: Spicy Food Does Not Equal Hot Returns

Using the metaphor of spicy food, Zweig examines the allure and dangers of high-risk, high-reward investments. He argues that while the thrill of chasing “hot” returns can be intoxicating, it often leads to disaster. Zweig cites studies showing that investors who chase performance—buying last year’s winners—consistently underperform those who stick to a disciplined, diversified strategy. He also provides examples of speculative manias, from dot-com stocks in 2000 to cryptocurrencies in 2017 and 2021, where fortunes were made and lost in months.

Zweig warns that high-risk investments are more likely to result in significant losses than life-changing gains. He notes that the psychological temptation to “go big or go home” is fueled by stories of overnight millionaires, but the reality is that most speculators end up losing money. The chapter includes data on the dismal long-term returns of lottery-like investments and penny stocks, which often go to zero.

For practical application, Zweig advises investors to assess their true risk tolerance and avoid investments that exceed their comfort level. He recommends building a balanced portfolio of stocks, bonds, and cash, and resisting the urge to chase the latest fad. If you do invest in speculative assets, limit them to a small “fun money” account and never risk money you can’t afford to lose.

Historically, every market cycle has included a “hot” sector or asset class that later crashes—think housing in 2006, cannabis stocks in 2018, or SPACs in 2021. Zweig’s advice is to prioritize safety and stability, even if it means missing out on the next big thing. In today’s world of social media-driven hype, his message is more relevant than ever.

Chapter 15: WACronyms: Why Initials Are So Often the Beginning of the End

Zweig discusses the proliferation of financial products with catchy acronyms—CDOs, ETFs, SPACs, and more—and why they often signal danger for investors. He explains that these products are typically complex, poorly understood, and heavily marketed. Zweig provides examples from the 2008 financial crisis, when CDOs (Collateralized Debt Obligations) were sold as safe investments but turned out to be toxic, causing massive losses for individuals and institutions alike.

He notes that acronyms are often used to make complex products seem simple and mainstream, masking underlying risks. Zweig warns that investors who buy products based on marketing rather than understanding are likely to be disappointed. He gives data on the explosion of ETF offerings—from a handful in the 1990s to thousands today—many of which are thinly traded, expensive, or highly leveraged.

For investors, Zweig’s advice is to avoid products you don’t fully understand, regardless of how appealing the name or marketing may be. He recommends focusing on simple, transparent investments with clear structures and proven track records. Before buying any product with an acronym, read the prospectus, understand the risks, and ask tough questions about costs and liquidity.

Historically, financial innovation has often preceded crisis—think mortgage-backed securities in 2007 or structured notes in the 1990s. Zweig’s skepticism is echoed by regulators and consumer advocates, who warn that complexity is rarely the investor’s friend. In today’s market, where new products appear daily, Zweig’s call for simplicity and transparency is essential for safe investing.

Chapter 16: Sex

In this provocative chapter, Zweig explores the psychological and emotional aspects of investing, drawing parallels between financial decision-making and human behavior related to sex. He discusses how emotions like desire, greed, and fear can override rational thought, leading to impulsive and destructive investment choices. Zweig uses examples of market bubbles where mass euphoria led investors to ignore risk—such as the internet boom of the late 1990s and the housing bubble of the mid-2000s.

He cites research from behavioral finance showing that the same brain regions activated by sexual desire are also triggered by the prospect of financial gain. This explains why investors often “fall in love” with certain stocks or strategies, ignoring warning signs and doubling down on losing bets. Zweig warns that overconfidence—believing you are immune to loss—can be as dangerous in investing as it is in personal relationships.

To counter these impulses, Zweig recommends developing self-awareness and discipline. He suggests creating rules for buying and selling, sticking to them regardless of market excitement, and seeking feedback from trusted advisors. Practicing mindfulness and taking time to reflect before making decisions can help investors avoid emotional traps.

Historically, the greatest financial disasters have been fueled by emotion, not logic. From the South Sea Bubble in 1720 to the meme stock frenzy of 2021, crowd psychology has repeatedly led investors astray. Zweig’s message: recognize your emotional triggers, and build systems to protect yourself from your own worst instincts. In an age of 24/7 news and social media, this lesson is more important than ever.

Chapter 17: Mind Control

Zweig delves deeper into the importance of psychological resilience and self-discipline in investing. He explains that the most successful investors are those who can control their minds and resist reacting emotionally to market fluctuations. Zweig discusses common cognitive biases—such as confirmation bias (seeking information that supports your beliefs) and loss aversion (fearing losses more than valuing gains)—and how they lead to poor decisions.

He provides examples of investors who sold at the bottom of the 2008 crisis, only to miss the subsequent recovery. Zweig suggests strategies for developing better self-control, such as setting clear, long-term goals, avoiding overexposure to financial news, and practicing mindfulness. He recommends periodic “media fasts” and automated investing to reduce the temptation to tinker with your portfolio.

Practically, Zweig advises creating checklists for investment decisions, reviewing them before making changes, and seeking accountability from a trusted friend or advisor. He also suggests keeping a journal of investment decisions and outcomes to identify patterns of behavior and improve discipline over time.

Historically, the best investors—like Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger—are known for their emotional stability and rational decision-making. Zweig’s focus on mind control is validated by research showing that disciplined, long-term investors consistently outperform those who react to short-term noise. In today’s hyper-connected world, where market news is constant, building psychological resilience is a critical edge.

Chapter 18: Financial Planning Fakery

Zweig critiques the financial planning industry, exposing common pitfalls and deceptive practices that can mislead investors. He explains that some financial advisors prioritize their own commissions over clients’ interests, recommending products that pay the highest fees rather than those best suited for the client. Zweig provides data showing that “fee-based” advisors often earn more from selling annuities or mutual funds than from providing unbiased advice.

He shares stories of investors who followed conflicted advice and ended up with expensive, underperforming portfolios. Zweig emphasizes the importance of understanding how your advisor is compensated and seeking out fiduciaries—advisors legally bound to act in your best interest. He also recommends learning basic financial principles so you can evaluate advice critically and avoid being misled by jargon or sales tactics.

For practical steps, Zweig suggests interviewing multiple advisors, asking for full disclosure of fees and conflicts, and demanding a written fiduciary oath. He encourages investors to use online tools and independent research to verify recommendations and avoid high-cost, commission-based products.

Historically, scandals like the 2016 Department of Labor fiduciary rule debate and the ongoing controversy over “suitability” versus “fiduciary” standards highlight the need for vigilance. Zweig’s advice is echoed by consumer advocates and regulators who urge investors to take control of their financial futures. In an industry rife with conflicts, education and skepticism are your best defenses.

Chapter 19: Advice on Advice

Zweig offers insights on how to evaluate and use financial advice effectively. He explains that not all advice is created equal, and that investors must be discerning about the sources and motivations behind the guidance they receive. Zweig discusses the wide range of advice available—from media pundits and online forums to professional advisors—and highlights the dangers of following crowd opinion or hype.

He provides examples of conflicting advice during market crises, such as the 2008 meltdown, when some experts urged panic selling while others recommended buying. Zweig emphasizes the importance of evidence-based advice, grounded in data and historical performance rather than speculation or marketing. He encourages investors to align advice with their own goals and risk tolerance, rather than blindly following popular opinion.

For practical application, Zweig suggests developing a checklist for evaluating advice: consider the source, credentials, potential conflicts, and track record. He recommends seeking multiple perspectives and using critical thinking to separate signal from noise. Investors should also document their decisions and review outcomes to improve their judgment over time.

Historically, the proliferation of financial media and online “experts” has made it harder than ever to distinguish good advice from bad. Zweig’s call for skepticism and self-reliance is validated by countless examples of investors burned by following gurus or market pundits. In today’s information-overloaded world, critical thinking is essential for investment success.

Chapter 20: Fraudian Psychology

Drawing on Freudian psychology, Zweig examines how subconscious desires and fears influence financial decisions. He explains that past experiences, emotions, and mental biases can lead to irrational behavior in the markets. Zweig provides examples of investors who panic during downturns or chase fads during bubbles, driven by deep-seated fears of missing out or losing status.

He discusses the importance of self-awareness, suggesting that investors reflect on their motivations and recognize when emotions are driving decisions. Zweig recommends strategies such as setting clear rules, maintaining a long-term perspective, and seeking feedback from trusted advisors to counteract psychological barriers. He also encourages regular reviews of assumptions and beliefs to avoid falling into emotional traps.

Practically, Zweig advises creating a disciplined investment plan, sticking to it during periods of stress, and using tools like automatic rebalancing to avoid knee-jerk reactions. He suggests practicing mindfulness and journaling to identify patterns of emotional decision-making and improve self-control over time.

Historically, the greatest market bubbles and crashes have been fueled by collective emotion—fear and greed—rather than fundamentals. Zweig’s insights are supported by behavioral finance research, which shows that self-aware, disciplined investors outperform those driven by emotion. In today’s volatile markets, understanding your psychological tendencies is a key to long-term success.

Chapter 21: The Terrible Tale of the Missing $10 Trillion

Zweig recounts the story of how trillions of dollars in wealth can disappear during financial crises, highlighting the risks of market bubbles and speculative investing. He uses historical examples such as the dot-com bubble (when the NASDAQ lost over 80% from its 2000 peak) and the 2008 financial crisis (which erased over $10 trillion in global wealth) to illustrate how quickly euphoria can turn to panic and massive losses.

He explains that speculative bubbles are driven by crowd psychology, FOMO (fear of missing out), and the belief that “this time is different.” Zweig provides data on the rapid rise and fall of asset prices, showing that markets can remain irrational longer than investors can remain solvent. He warns that chasing trends or trying to time the market is a recipe for disaster.

For investors, Zweig recommends focusing on fundamentals, maintaining a disciplined, long-term strategy, and avoiding speculative fads. He suggests using historical perspective to recognize when markets are overheating and having the courage to sit out manias, even if it means missing short-term gains. Regular portfolio reviews and adherence to a written investment plan can help avoid the temptation to chase bubbles.

Historically, every major crisis—from the South Sea Bubble to the 2008 meltdown—has followed the same pattern of boom, bust, and regret. Zweig’s cautionary tale is a powerful reminder that the best way to survive market storms is to avoid getting caught up in the frenzy. In today’s world of rapid innovation and social media-driven hype, this lesson is as relevant as ever.

Chapter 22: How to Talk Back to Market Baloney

In the final chapter, Zweig empowers readers to recognize and refute common myths, misconceptions, and misleading information in the financial markets. He explains how financial news, advertisements, and market commentary are often designed to manipulate investor behavior, rather than educate. Zweig provides examples of “market baloney,” such as promises of guaranteed returns, quick fixes, or secret strategies, and teaches readers how to spot red flags.

He emphasizes the importance of skepticism and critical analysis, suggesting that investors question the motives behind every piece of advice or product pitch. Zweig recommends focusing on evidence-based strategies, grounded in historical data and proven principles, rather than chasing trends or responding to hype. He encourages readers to develop the habit of verifying information before acting and to seek out multiple perspectives.

Practically, Zweig advises creating a checklist for evaluating market commentary, looking for conflicts of interest, and ignoring sensational headlines. He suggests building a network of trusted sources and using independent research to validate claims. By prioritizing rational, evidence-based investing, readers can protect themselves from manipulation and make better decisions.

Historically, market manias and panics have been fueled by misinformation and hype, from the “Nifty Fifty” stocks of the 1970s to the crypto and meme stock crazes of recent years. Zweig’s final message is that the best defense against market baloney is a disciplined, skeptical, and well-informed approach. In a world awash with noise, those who think critically will be the most successful investors.

Advanced Strategies from the Book

While The Little Book of Safe Money is focused on conservative, foundational principles, Zweig also offers advanced techniques for investors seeking to further optimize their portfolios. These strategies are designed for those who have mastered the basics and want to fine-tune their approach for greater tax efficiency, risk management, and behavioral discipline. Zweig’s advanced tactics are rooted in the same philosophy of safety, skepticism, and long-term thinking, but require a deeper understanding of financial instruments and investor psychology.

Many of these techniques involve using modern tools—such as tax-loss harvesting, asset location, and systematic rebalancing—to enhance returns and reduce risk without sacrificing safety. Zweig also addresses advanced behavioral strategies, such as pre-commitment devices and accountability systems, to help investors stick to their plans in the face of market turbulence. Below are several of the most valuable advanced strategies from the book, with detailed explanations and real-world examples.

Strategy 1: Tax-Loss Harvesting and Asset Location

Tax-loss harvesting involves selling investments that have declined in value to offset gains elsewhere in your portfolio, reducing your overall tax bill. Zweig explains that by systematically realizing losses and reinvesting the proceeds, investors can improve after-tax returns without altering their risk profile. For example, if you have a $5,000 gain in one stock and a $5,000 loss in another, selling both allows you to avoid paying capital gains tax. Zweig also recommends asset location—placing tax-inefficient investments (like bonds and REITs) in tax-advantaged accounts (IRAs, 401(k)s), while holding tax-efficient assets (like index funds) in taxable accounts. This strategy can add up to 1% per year in after-tax returns, compounding into substantial wealth over decades.

Strategy 2: Systematic Rebalancing and Pre-Commitment Devices

Zweig advocates for systematic rebalancing—periodically adjusting your portfolio back to target allocations—to maintain discipline and avoid emotional decision-making. He suggests setting calendar-based or threshold-based triggers (e.g., rebalance every six months or when an asset class deviates by more than 5% from target). Pre-commitment devices, such as automatic rebalancing or written investment policies, help investors resist the urge to chase performance or panic during downturns. Zweig notes that disciplined rebalancing forces you to “buy low and sell high” by trimming winners and adding to laggards, enhancing long-term returns and reducing risk.

Strategy 3: Behavioral Accountability and Investment Journaling

To counteract psychological biases, Zweig recommends building accountability systems and keeping an investment journal. By documenting every investment decision, the rationale, and the outcome, investors can identify patterns of emotional or impulsive behavior and improve over time. Zweig suggests sharing your investment plan and goals with a trusted friend or advisor, creating a social contract that reinforces discipline. Research shows that investors who keep journals and seek feedback are less likely to make costly mistakes and more likely to stick to their strategies during market turbulence.

Strategy 4: Laddering and Duration Management in Fixed Income

For bond investors, Zweig recommends laddering—building a portfolio of bonds with staggered maturities—to reduce interest rate risk and provide regular liquidity. This approach ensures that a portion of the portfolio matures each year, allowing reinvestment at current rates and reducing the impact of rising or falling yields. Zweig also advises managing the average duration of the bond portfolio, keeping it short in rising rate environments and extending it when rates are stable or falling. This advanced technique helps maintain stability and preserve purchasing power, especially in volatile markets.

Strategy 5: Factor Diversification and Smart Beta

While Zweig is skeptical of most “smart beta” and factor-based products, he acknowledges that diversifying across proven risk factors—such as value, size, and quality—can enhance returns without adding significant risk. He recommends using low-cost ETFs or index funds that tilt toward value stocks, small caps, or high-quality companies, but warns against overpaying for complexity or chasing the latest trend. By combining traditional asset allocation with selective factor exposure, investors can build more resilient portfolios that capture multiple sources of return over time.

Most investors waste time on the wrong metrics. We've spent 10,000+ hours perfecting our value investing engine to find what actually matters.

Want to see what we'll uncover next - before everyone else does?

Find Hidden Gems First!

Implementation Guide

Starting to apply the lessons from The Little Book of Safe Money requires a shift in both mindset and practice. Zweig’s approach is not about chasing quick wins, but about building a resilient, low-cost, and well-diversified portfolio that can withstand market shocks and behavioral pitfalls. The first step is to internalize the book’s core commandments—avoid unnecessary risk, only take risks likely to be rewarded, and never risk more than you can afford to lose. From there, investors can build a practical plan using the tools and strategies outlined above.

Implementation begins with an honest assessment of your risk tolerance, time horizon, and financial goals. Zweig recommends writing down your investment plan, including target allocations, rebalancing rules, and behavioral safeguards. Regular reviews and adjustments are essential, but should be driven by changes in your life circumstances, not by market headlines or hype. By focusing on simplicity, transparency, and discipline, investors can avoid the traps that ensnare so many and build lasting wealth over time.

- First step investors should take: Assess your current portfolio for unnecessary risks, lack of liquidity, and excessive fees. Identify areas where you are overexposed—such as too much in your own company’s stock or high-yield products—and begin reallocating to safer, more diversified assets.

- Second step for building the strategy: Create a written investment plan with clear goals, target allocations, and rules for rebalancing. Set up automatic contributions to low-cost index funds or ETFs, and establish a liquidity buffer in insured savings or short-term Treasuries.

- Third step for long-term success: Regularly review your portfolio, investment plan, and behavioral patterns. Use tax-efficient strategies, systematic rebalancing, and accountability tools to stay disciplined. Adjust your plan only when your life circumstances change, not in response to market noise.

Critical Analysis

The Little Book of Safe Money excels at distilling complex investment principles into clear, actionable advice. Zweig’s writing is engaging, witty, and filled with memorable metaphors that make the lessons stick. The book’s greatest strength is its focus on behavioral finance—the psychological traps that cause investors to make costly mistakes. Zweig’s real-world examples and historical context bring the lessons to life, while his skepticism of Wall Street marketing and product complexity is a refreshing antidote to industry hype.

However, the book’s conservative approach may not appeal to aggressive investors seeking outsized returns or those looking for detailed guidance on advanced strategies. Zweig’s emphasis on safety and skepticism can sometimes border on caution fatigue, potentially discouraging risk-taking where appropriate. The book also spends less time on practical asset allocation models or specific fund recommendations, focusing instead on principles and mindset. For readers seeking a step-by-step investment blueprint, supplemental reading may be necessary.

In today’s market environment—characterized by increased volatility, product proliferation, and behavioral pitfalls—Zweig’s message is more relevant than ever. The rise of meme stocks, crypto speculation, and leveraged products makes the need for discipline, skepticism, and humility paramount. The Little Book of Safe Money is a timely reminder that the best way to build wealth is to avoid big mistakes, keep costs low, and stay focused on the long term.

Conclusion

The Little Book of Safe Money is a must-read for anyone seeking to protect and grow their wealth in an uncertain world. Jason Zweig’s blend of psychological insight, market history, and practical advice provides a comprehensive roadmap for safe, disciplined investing. The book’s core message—prioritize safety, avoid unnecessary risk, and focus on what you can control—is timeless and universally applicable.

Whether you’re a novice investor, a retiree, or a seasoned market participant, Zweig’s lessons will help you avoid the traps that destroy wealth and build a portfolio that can weather any storm. By internalizing the book’s commandments, embracing simplicity, and practicing behavioral discipline, you can achieve lasting financial success—without losing sleep or falling for the market’s endless hype. The Little Book of Safe Money deserves a place on every investor’s bookshelf.

--- ---

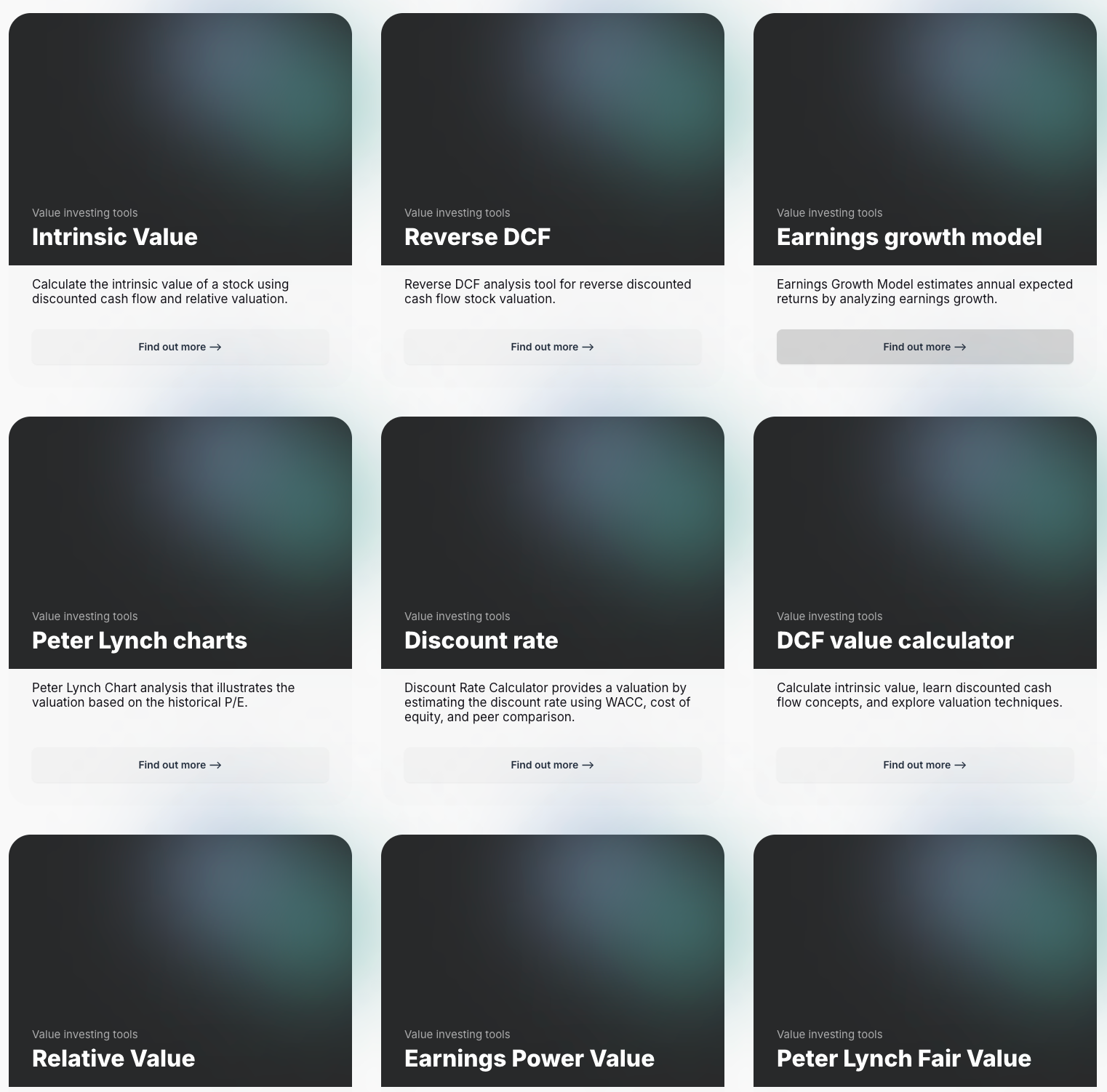

10+ Free intrinsic value tools

For investors looking to find a stock's fair value, our analytics team has you covered with intrinsic value tools:

📍 Free Intrinsic Value Calculator

📍 Reverse DCF & DCF value tools

📍 Peter Lynch Fair Value Calculator

📍 Ben Graham Fair Value Calculator

📍 Relative Value tool

...and plenty more.

🔍 Explore all these tools for free on the Value Sense platform and start discovering what your favorite stocks are really worth.

FAQ: Common Questions About The Little Book of Safe Money

1. Who is Jason Zweig, and why should I trust his advice?

Jason Zweig is a respected financial journalist, longtime Wall Street Journal columnist, and the editor of Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor. He is renowned for his deep understanding of behavioral finance and his ability to translate complex investment concepts into practical, actionable advice. Zweig’s decades of experience and commitment to investor education make him a trusted authority in the field.

2. What is the main message of The Little Book of Safe Money?

The book’s central message is to prioritize safety, avoid unnecessary risks, and focus on long-term wealth preservation. Zweig emphasizes that the best way to build wealth is to avoid big mistakes, keep costs low, and maintain a disciplined, skeptical approach to investing. He teaches readers how to recognize and avoid the psychological, structural, and product-based traps that can erode wealth.

3. Is this book only for conservative or risk-averse investors?

While the book is particularly valuable for conservative or risk-averse investors, its lessons are universal. Zweig’s principles of diversification, behavioral discipline, and skepticism are relevant for investors of all risk tolerances. Even aggressive investors can benefit from understanding the importance of capital preservation and the dangers of overconfidence.

4. Does the book provide specific investment recommendations?

Zweig focuses more on principles and mindset than on specific securities or funds. He provides guidelines for asset allocation, product selection, and risk management, but does not endorse individual stocks or funds. For detailed portfolio construction advice, readers may wish to supplement the book with other resources or consult a fiduciary advisor.

5. How does The Little Book of Safe Money differ from other investment books?

The book stands out for its focus on psychological traps, behavioral finance, and the dangers of product complexity. Zweig’s use of metaphors, real-world examples, and historical context makes the lessons memorable and actionable. Unlike many investment books that chase the latest trend, Zweig’s approach is timeless and grounded in evidence-based principles.

6. What practical steps can I take after reading this book?

After reading, assess your portfolio for unnecessary risks, create a written investment plan, and focus on low-cost, diversified investments. Build a liquidity buffer, avoid yield chasing, and set up systematic rebalancing. Regularly review your plan and stay vigilant for behavioral traps and product hype.

7. Is The Little Book of Safe Money still relevant in today’s market?

Absolutely. In an environment of heightened volatility, product innovation, and social media-driven speculation, Zweig’s focus on safety, skepticism, and discipline is more important than ever. The book’s timeless principles help investors navigate both bull and bear markets with confidence and resilience.

8. Can young investors benefit from this book, or is it mainly for retirees?

Young investors can gain tremendous value from Zweig’s lessons. By learning to avoid big mistakes early, building good habits, and embracing long-term discipline, young investors can harness the power of compounding and achieve greater financial security over their lifetimes.

9. How does the book address behavioral finance and psychology?

Zweig devotes multiple chapters to the psychological traps that derail investors, such as overconfidence, loss aversion, and herd mentality. He offers practical tools for developing self-awareness, discipline, and resilience—skills that are essential for long-term investment success.

10. Where can I find more resources and tools to implement the book’s strategies?

Visit Value Sense for research tools, intrinsic value calculators, and stock ideas that align with Zweig’s philosophy. The platform offers educational resources, watchlists, and analytics to help you build and manage a safer, more effective investment portfolio.