Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Welcome to the Value Sense Blog, your resource for insights on the stock market! You're reading a book review written by the valuesense.io team.

On our platform, you'll find stock research and insights across all sectors. Dive into our research products and learn more about our unique approach at valuesense.io

We offer over 360+ automated stock ideas, a free AI-powered stock screener, interactive stock charting tools, and more than 10 intrinsic value models — all designed to help investors find undervalued growth opportunities.

Book Overview

"Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman stands as one of the most influential books in both psychology and investment literature. Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel laureate in Economic Sciences, is renowned for his pioneering work in behavioral economics and cognitive psychology. Alongside his collaborator Amos Tversky, Kahneman fundamentally changed our understanding of decision making, challenging the traditional economic assumption that humans are rational actors. His research, which earned him the Nobel Prize in 2002, has had a profound impact not only on economics but also on finance, investing, and public policy.

Published in 2011, "Thinking, Fast and Slow" encapsulates decades of research into how humans think, decide, and err. The book emerged in a post-financial crisis world, when investors and policymakers were questioning the rationality of markets and the limits of human judgment. Kahneman’s work provided a timely framework for understanding how cognitive biases and mental shortcuts—heuristics—shape our decisions, often in ways that deviate from classical economic theory. The book’s historical context is critical: it arrived at a time when behavioral finance was gaining traction, and its insights have since become foundational for anyone seeking to understand market psychology.

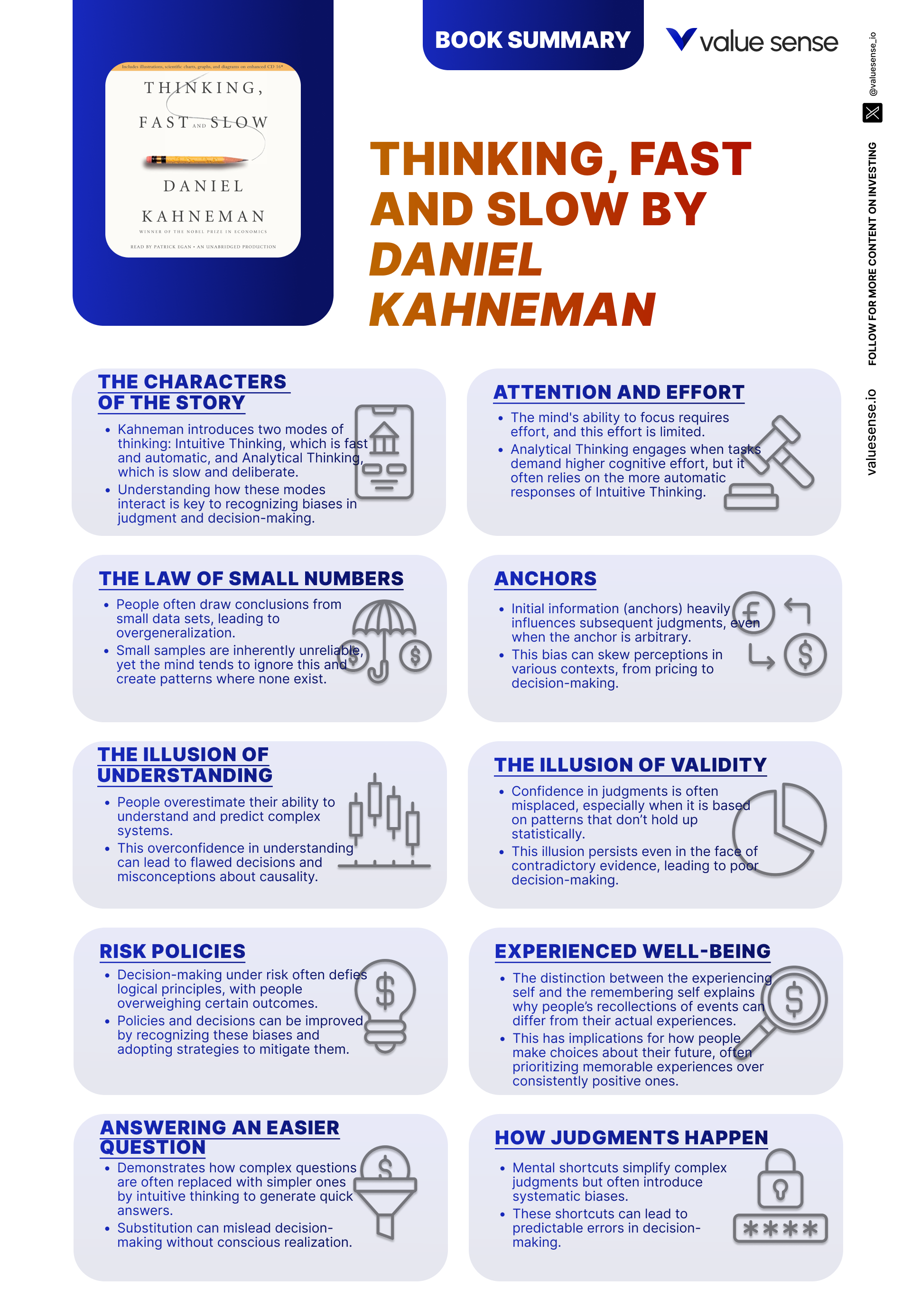

The core theme of the book is the interplay between two modes of thinking: System 1, which is fast, intuitive, and automatic; and System 2, which is slow, deliberate, and analytical. Kahneman meticulously demonstrates how these systems interact, sometimes harmoniously but often in conflict, leading to systematic errors in judgment. Through vivid examples and groundbreaking experiments, he reveals the hidden mechanisms behind our choices, from everyday decisions to high-stakes investment moves.

"Thinking, Fast and Slow" is considered a classic because it bridges psychology, economics, and practical investing with unparalleled clarity. It offers a comprehensive map of the human mind, exposing the predictable ways we misjudge probabilities, misread risks, and fall prey to overconfidence. Investors, in particular, find immense value in Kahneman’s insights, as the book provides tools to recognize and mitigate the cognitive traps that can undermine rational portfolio management. It’s not just a book for academics—its lessons are immediately actionable for anyone managing money, making business decisions, or seeking to improve their judgment under uncertainty.

What sets this book apart from other investment classics is its scientific rigor and its focus on the psychological roots of decision making. While many investment books offer strategies and rules of thumb, Kahneman’s work digs deeper, explaining why those rules sometimes fail and how our minds can betray us. The book is essential reading for investors, financial professionals, business leaders, and lifelong learners who want to understand the true drivers of human behavior. Its unique blend of storytelling, empirical evidence, and actionable wisdom makes it a must-read for anyone aiming to outthink the market—or themselves.

Key Themes and Concepts

"Thinking, Fast and Slow" weaves together a series of powerful themes that illuminate the complexities of human judgment and decision making. These themes are not merely academic—they have direct implications for investors, business leaders, and anyone who must make choices under uncertainty. Kahneman’s exploration of these ideas reveals why even the most intelligent individuals can fall prey to predictable errors, and how understanding these patterns can lead to better outcomes in both investing and life.

Throughout the book, Kahneman returns to several core concepts: the dual-system model of thinking, the pervasive influence of heuristics and biases, the dangers of overconfidence, the quirks of decision making under risk, and the distinction between our experiencing and remembering selves. Each theme is supported by decades of research, real-world examples, and practical advice for mitigating the pitfalls of human cognition. By mastering these themes, investors can cultivate a more disciplined, self-aware approach to decision making, gaining an edge over the competition.

- Two Systems of Thinking: The foundational theme of the book is the interplay between System 1 (fast, intuitive, automatic) and System 2 (slow, deliberate, effortful). System 1 excels at pattern recognition and quick responses but is prone to errors when faced with complex or unfamiliar problems. System 2, while slower and more resource-intensive, is capable of logical reasoning and critical analysis. Kahneman illustrates how most of our daily decisions are governed by System 1, with System 2 intervening only when necessary. For investors, recognizing when to engage System 2—such as during portfolio analysis or risk assessment—is crucial for avoiding costly mistakes. The tension between these systems explains why even seasoned professionals can make irrational choices, especially under stress or cognitive load.

- Heuristics and Biases: Kahneman delves deeply into the mental shortcuts, or heuristics, that our brains use to simplify complex decisions. While heuristics can be efficient, they often lead to systematic biases, such as the availability heuristic (overweighting recent or vivid events), representativeness (judging probabilities based on stereotypes), and anchoring (relying too heavily on initial information). These biases can distort investment decisions, leading to overreaction to news, mispricing of risk, and herd behavior. The book provides numerous examples, such as how investors might overestimate the likelihood of market crashes after a recent downturn, or anchor on irrelevant price targets. Understanding these biases allows investors to implement safeguards, such as checklists and decision journals, to counteract their effects.

- Overconfidence: One of the most dangerous biases in investing is overconfidence—the tendency to overestimate our knowledge, abilities, and predictive power. Kahneman explores how the illusion of understanding and hindsight bias can lead investors to believe they have more control over outcomes than they actually do. This can result in excessive trading, underestimation of risks, and failure to diversify. The book highlights studies showing that expert predictions are often no more accurate than chance, yet experts remain highly confident in their forecasts. For investors, cultivating humility and skepticism is essential, as is relying on probabilistic thinking rather than certainty.

- Decision Making Under Risk: Kahneman’s introduction of prospect theory revolutionized our understanding of how people make choices under uncertainty. Unlike traditional economic models, which assume rational actors maximize expected utility, prospect theory shows that people are loss averse—they feel the pain of losses more acutely than the pleasure of gains. This leads to risk-averse behavior in gains and risk-seeking behavior in losses, explaining phenomena such as the disposition effect (selling winners too early and holding losers too long). The book provides practical frameworks for recognizing and managing these tendencies, such as pre-committing to rules-based strategies and focusing on long-term outcomes rather than short-term fluctuations.

- The Two Selves: In the later chapters, Kahneman introduces the distinction between the experiencing self (which lives in the present moment) and the remembering self (which constructs the narrative of our lives). These two selves often have conflicting preferences, leading to decisions that maximize remembered satisfaction rather than actual well-being. For investors, this insight is critical when evaluating performance and setting goals. Chasing memorable wins or avoiding memorable losses can distort long-term strategy. Understanding the two selves helps investors align their actions with genuine objectives, rather than fleeting emotions or misleading memories.

- Framing and Context Effects: The way choices are presented—framed—can dramatically influence decisions. Kahneman demonstrates that identical options can yield different choices depending on whether they are framed as gains or losses. This has profound implications for investment communication, product design, and risk disclosure. For example, investors may react differently to a fund described as “80% likely to outperform” versus “20% likely to underperform,” even though the information is equivalent. Mastery of framing effects enables investors to make more consistent, rational choices and to communicate more effectively with clients and stakeholders.

- Limits of Expert Intuition: Throughout the book, Kahneman questions the reliability of expert intuition, especially in unpredictable environments like financial markets. He distinguishes between domains where intuition can be trusted (stable, predictable patterns) and those where it cannot (noisy, chaotic systems). The book urges investors to rely on statistical models and disciplined processes rather than gut feelings, particularly when the stakes are high and feedback is delayed. This theme reinforces the importance of evidence-based investing and ongoing learning.

Book Structure: Major Sections

Part 1: Two Systems

This opening section (Chapters 1–5) introduces the dual-system model of cognition, laying the groundwork for the entire book. Kahneman delineates System 1, the fast, automatic, and intuitive mode of thinking, from System 2, the slow, effortful, and analytical mode. The interplay between these two systems is the lens through which all subsequent biases and decision-making errors are examined. The section explores how these systems operate in tandem, sometimes cooperating but often at odds, leading to both efficient judgments and costly mistakes.

Key concepts include the effortless pattern recognition of System 1 and the deliberate reasoning of System 2. Kahneman provides vivid examples, such as quickly solving simple math problems (System 1) versus tackling complex calculations (System 2). He demonstrates that while System 1 is indispensable for navigating daily life, it can mislead us in unfamiliar or complex scenarios. The section also introduces cognitive ease, showing how our comfort with information can lull us into faulty reasoning. For investors, this means that gut feelings and snap judgments can be valuable in certain contexts but are dangerous when analyzing complex financial data.

Investors can apply these insights by cultivating awareness of when each system is at work. Implementing decision-making checklists, pausing before major trades, and seeking diverse perspectives can help engage System 2 when it matters most. Recognizing the limits of intuition is crucial for avoiding impulsive trades and overreacting to market noise.

In today’s fast-paced markets, the two-systems framework remains highly relevant. With information overload and algorithmic trading increasing the speed of decision making, investors must be vigilant about when to trust their instincts versus when to slow down and analyze. The enduring lesson is that disciplined, reflective thinking is a competitive advantage in an environment dominated by noise and emotion.

Part 2: Heuristics and Biases

Chapters 6–10 delve into the mental shortcuts, or heuristics, that our brains use to simplify complex decisions. These heuristics, while often useful, can lead to systematic errors—biases—that distort our perceptions and judgments. Kahneman examines biases such as availability, representativeness, and anchoring, illustrating how they arise from the interplay of the two systems. This section is foundational for understanding why even well-informed investors can make irrational choices.

Key concepts include the availability heuristic (overweighting recent or vivid events), representativeness (judging probabilities based on stereotypes), and anchoring (relying too heavily on initial information). Kahneman uses examples such as investors overreacting to recent market crashes or anchoring on arbitrary price targets. These biases can lead to herd behavior, mispricing of risk, and suboptimal portfolio decisions. The section also explores the limits of human memory and the tendency to seek patterns where none exist.

To mitigate these biases, investors should use structured decision processes, such as pre-commitment strategies and decision journals. Regularly reviewing past decisions and outcomes can help identify recurring errors. Relying on quantitative models and objective criteria, rather than intuition alone, reduces the influence of cognitive shortcuts.

With the proliferation of financial news and data, the relevance of heuristics and biases has only increased. Social media amplifies vivid events, increasing the risk of availability bias. Understanding these pitfalls is essential for maintaining discipline in volatile markets and for distinguishing signal from noise in an era of information overload.

Part 3: Overconfidence

This section (Chapters 19–23) explores the pervasive human tendency toward overconfidence, particularly in our own knowledge, abilities, and predictions. Kahneman dissects the illusion of understanding and the illusion of validity, showing how narratives and hindsight bias contribute to unwarranted certainty. The section is a sobering reminder that confidence is not always correlated with accuracy, especially in complex, unpredictable domains like investing.

Kahneman presents compelling evidence that expert predictions are often no more accurate than random guesses, yet experts remain highly confident in their forecasts. He discusses the dangers of hindsight bias—believing events were predictable after the fact—and the tendency to construct coherent narratives from random outcomes. These illusions can lead to excessive trading, under-diversification, and misallocation of capital. The section also explores the limits of intuition in noisy, feedback-poor environments.

Investors can counteract overconfidence by embracing probabilistic thinking, diversifying portfolios, and relying on evidence-based processes. Regularly calibrating confidence levels with actual outcomes, seeking disconfirming evidence, and using statistical models can help maintain humility. Avoiding narrative-driven investing and focusing on long-term probabilities are practical steps to reduce the risks of overconfidence.

In an age of 24/7 financial media and expert punditry, the dangers of overconfidence are more pronounced than ever. The illusion of understanding persists, fueled by data analytics and storytelling. Kahneman’s warning is timeless: humility, skepticism, and a disciplined approach are essential for navigating the uncertainties of modern markets.

Part 4: Choices

Chapters 25–29 examine how people make decisions under risk and uncertainty, introducing prospect theory as a revolutionary alternative to traditional economic models. Kahneman explains how framing, context, and loss aversion shape our choices, often leading to inconsistent and irrational behavior. This section is particularly relevant for investors, as it addresses the psychological drivers of risk-taking and portfolio management.

Key concepts include the value function of prospect theory, which is steeper for losses than for gains, explaining why losses hurt more than equivalent gains please. The section also explores the endowment effect (overvaluing what we own), mental accounting, and the impact of framing on risk preferences. Kahneman provides real-world examples of how investors sell winners too early (risk-averse in gains) and hold onto losers too long (risk-seeking in losses). He also discusses the disposition effect and the influence of context on risk assessment.

Investors can apply these lessons by setting predefined rules for selling and buying, focusing on long-term objectives, and avoiding emotional reactions to short-term fluctuations. Using stop-loss orders, rebalancing portfolios systematically, and employing mental accounting can help manage risk more effectively. Being aware of framing effects enables more consistent decision making.

Prospect theory has become a cornerstone of behavioral finance, deeply influencing how investment products are designed and how advisors communicate with clients. The insights from this section remain highly relevant in today’s volatile markets, where loss aversion and framing effects can lead to suboptimal decisions. Understanding these psychological drivers is essential for constructing resilient, rational portfolios.

Part 5: Two Selves

The final section (Chapters 35–38) explores the distinction between the experiencing self and the remembering self, and how this affects our perceptions of happiness, satisfaction, and well-being. Kahneman argues that these two selves often have conflicting priorities, leading to decisions that optimize remembered experiences rather than actual moment-to-moment happiness. This section broadens the book’s scope beyond investing, offering profound insights into life satisfaction and goal setting.

Key concepts include the peak-end rule (memories are shaped by the most intense and final moments of an experience), duration neglect, and the challenges of measuring true well-being. Kahneman uses examples from vacations, medical procedures, and financial outcomes to illustrate how the remembering self can dominate decision making. For investors, this explains why memorable gains or losses can disproportionately influence future choices, sometimes at the expense of long-term objectives.

Investors can use these insights to align their strategies with genuine goals, rather than chasing memorable wins or avoiding memorable losses. Regularly reviewing performance in terms of long-term objectives, rather than episodic highs and lows, can help maintain discipline. Understanding the two selves also aids in setting realistic expectations and avoiding regret-driven decisions.

As financial technology enables more frequent performance tracking and sharing, the tension between the experiencing and remembering selves is more pronounced than ever. Kahneman’s framework helps investors—and anyone seeking satisfaction—navigate the complexities of memory, emotion, and long-term well-being in a world obsessed with short-term results.

Deep Dive: Essential Chapters

Chapter 1: The Characters of the Story

This opening chapter is critically important because it introduces the dual-system model—System 1 and System 2—that forms the backbone of the entire book. Kahneman sets the stage by describing how these two systems govern our thinking, with System 1 operating automatically and quickly, and System 2 engaging in slow, deliberate reasoning. The chapter establishes the foundational premise that much of our behavior is shaped by the interplay of these systems, often outside our conscious awareness. Understanding this framework is essential for grasping the subsequent discussions on heuristics, biases, overconfidence, and decision making under risk.

Kahneman provides vivid examples to illustrate the two systems at work. For instance, reading simple words or recognizing faces relies on System 1, while solving complex math problems or analyzing investment portfolios requires System 2. He explains that System 1 is always active, generating impressions and feelings, while System 2 is called upon when we encounter something unexpected or challenging. The chapter includes memorable quotes such as, “System 1 runs automatically and System 2 is normally in a comfortable low-effort mode.” Kahneman also introduces the idea that System 2 can be lazy, often accepting the suggestions of System 1 without sufficient scrutiny.

Investors can apply these lessons by developing an awareness of which system is driving their decisions at any given moment. Before making significant trades or portfolio adjustments, it’s wise to pause and engage System 2, questioning intuitive judgments and seeking additional data. Creating a checklist for major investment decisions helps ensure that analytical thinking is activated, reducing the risk of impulsive errors. Training oneself to recognize the signs of cognitive ease—when things feel too simple or obvious—can be a cue to slow down and scrutinize assumptions.

Historically, the two-system model has reshaped how financial professionals approach decision making. The rise of behavioral finance in the 1990s and 2000s was fueled by recognition of these cognitive dynamics. In modern markets, where information is abundant and decisions are made rapidly, the distinction between System 1 and System 2 is more relevant than ever. Investors who cultivate metacognitive awareness—thinking about their own thinking—are better equipped to navigate uncertainty and avoid costly mistakes.

Chapter 5: Cognitive Ease

This chapter is pivotal because it explores the concept of cognitive ease—the comfort we feel when processing familiar or fluent information—and its profound influence on our judgments and beliefs. Kahneman demonstrates that when information is easy to process, we are more likely to accept it as true, trust it, and act on it without critical analysis. This phenomenon underlies many common biases and errors, making it essential reading for investors seeking to improve their decision-making rigor.

Kahneman cites experiments showing that statements presented in clear, bold fonts are more readily believed than those in hard-to-read fonts. He explains that cognitive ease leads to positive feelings, increased trust, and reduced skepticism, while cognitive strain triggers System 2 and encourages critical thinking. The chapter provides examples such as repeated exposure to a stock ticker symbol increasing investor comfort and confidence, even in the absence of substantive information. Kahneman warns that cognitive ease can create a false sense of understanding and lead to overconfidence in superficial analyses.

For investors, the key application is to be wary of decisions made in states of cognitive ease. When information feels too familiar or persuasive, it’s important to introduce cognitive strain by seeking alternative viewpoints, challenging assumptions, and conducting deeper analysis. Using structured decision processes, such as investment memos and devil’s advocate reviews, can help counteract the seductive effects of cognitive ease. Investors should also be mindful of marketing tactics and media narratives designed to exploit cognitive comfort.

In the real world, cognitive ease explains why financial bubbles can form around familiar or trendy assets, and why investors can be lulled into complacency by positive market sentiment. The dot-com bubble, for example, was fueled in part by the repeated exposure to tech company names and optimistic narratives. By recognizing the role of cognitive ease, modern investors can safeguard against herd behavior and make more disciplined, evidence-based decisions.

Chapter 11: Anchors

The "Anchors" chapter is critically important as it examines the anchoring effect—a pervasive heuristic where initial exposure to a number or idea unduly influences subsequent judgments. Kahneman reveals how anchors can bias everything from price estimates to risk assessments, making this chapter essential for investors and financial professionals who routinely set targets, forecasts, and valuations.

Kahneman describes experiments where participants’ estimates of African nations in the United Nations were swayed by arbitrary numbers spun on a wheel. He explains that even irrelevant anchors can have a powerful pull on our judgments, leading to systematic errors. The chapter provides investment-specific examples, such as analysts anchoring on previous stock prices or earnings forecasts, and highlights how market participants can be influenced by opening prices, analyst targets, or recent highs and lows. Kahneman notes, “People adjust away from anchors, but the adjustment is usually insufficient.”

To mitigate anchoring bias, investors should deliberately seek out independent data and alternative scenarios before making decisions. Using multiple valuation methods, consulting diverse sources, and setting pre-defined criteria for buying or selling can help reduce the influence of anchors. Periodic reviews of decision processes can reveal when anchoring has crept in, enabling corrective action. Training teams to recognize and challenge anchors during investment committee meetings is another practical step.

Anchoring bias is evident in historical market events, such as the reluctance of investors to sell stocks that have fallen below their purchase price (anchoring on the original cost). In modern markets, the proliferation of analyst price targets and consensus estimates increases the risk of anchoring. By understanding this bias, investors can make more objective, data-driven decisions, avoiding the traps set by arbitrary or irrelevant reference points.

Chapter 19: The Illusion of Understanding

This chapter is essential because it delves into the illusion of understanding—a cognitive trap where we believe we comprehend complex phenomena more deeply than we actually do. Kahneman demonstrates how narratives, hindsight bias, and the human desire for coherence lead us to construct plausible but often inaccurate explanations for events, fostering overconfidence and flawed decision making.

Kahneman uses the example of stock market narratives that emerge after major events, such as crashes or rallies. He explains that, in hindsight, outcomes appear inevitable and predictable, even when they were highly uncertain at the time. The chapter presents research showing that people consistently overestimate their ability to predict outcomes and underestimate the role of luck and randomness. Kahneman writes, “What you see is all there is,” highlighting our tendency to ignore missing information and focus on coherent stories.

Investors can combat the illusion of understanding by embracing probabilistic thinking and acknowledging the limits of their knowledge. Regularly reviewing past decisions and considering alternative explanations for outcomes can foster humility. Using scenario analysis and stress testing helps account for uncertainty and reduces reliance on oversimplified narratives. Encouraging a culture of intellectual honesty and skepticism within investment teams is also crucial.

The illusion of understanding has contributed to major financial crises, such as the 2008 meltdown, where complex risks were underestimated due to overconfidence in prevailing narratives. In today’s data-rich environment, the temptation to construct neat stories from noisy data is greater than ever. By recognizing this illusion, investors can maintain a more realistic perspective on risk and uncertainty, improving long-term performance.

Chapter 25: Bernoulli’s Errors

This chapter is a turning point in the book, as it critiques the traditional economic model of expected utility theory, developed by Daniel Bernoulli. Kahneman exposes the limitations of this framework in explaining real-world decision making, setting the stage for the introduction of prospect theory—a more psychologically accurate model of human behavior under risk.

Kahneman explains that Bernoulli’s theory assumes people evaluate outcomes based on final wealth, using a consistent utility function. However, experiments reveal that people are far more sensitive to changes in wealth than to absolute levels, and that losses loom larger than gains. The chapter discusses the “reference point” effect, where people evaluate outcomes relative to a baseline, and the diminishing sensitivity to gains and losses as values increase. Kahneman provides data showing that expected utility theory fails to predict actual choices in scenarios involving risk and uncertainty.

For investors, the lesson is to recognize that traditional models may not capture the true drivers of behavior. Incorporating insights from behavioral finance—such as loss aversion and reference dependence—can improve portfolio construction and risk management. Investors should be cautious about relying solely on expected utility calculations and should consider the psychological impact of gains and losses on themselves and their clients.

The shortcomings of expected utility theory became glaringly apparent during financial crises, when investor behavior deviated sharply from rational models. Prospect theory, introduced in this chapter, has since become a cornerstone of modern finance, influencing everything from asset allocation to product design. Understanding Bernoulli’s errors equips investors to build strategies that are robust to the realities of human psychology.

---

Explore More Investment Opportunities

For investors seeking undervalued companies with high fundamental quality, our analytics team provides curated stock lists:

📌 50 Undervalued Stocks (Best) overall value plays for 2025

📌 50 Undervalued Dividend Stocks (For income-focused investors)

📌 50 Undervalued Growth Stocks (High-growth potential with strong fundamentals)

🔍 Check out these stocks on the Value Sense platform for free!

---

Chapter 26: Prospect Theory

This chapter is arguably the most important in the book, as it introduces prospect theory—a groundbreaking model that explains how people actually make decisions under risk. Kahneman and Tversky’s prospect theory challenges the rational actor model by incorporating psychological realities such as loss aversion, reference dependence, and diminishing sensitivity.

Kahneman outlines the key components of prospect theory: the value function (which is steeper for losses than for gains), the reference point (against which gains and losses are evaluated), and probability weighting (overweighting small probabilities and underweighting large ones). He provides experimental data showing that people are much more sensitive to potential losses than equivalent gains—a phenomenon known as loss aversion. The chapter contrasts prospect theory with expected utility theory, demonstrating its superior predictive power in real-world decision making.

Investors can apply prospect theory by designing portfolios and strategies that account for loss aversion. This might include setting stop-loss limits, diversifying to reduce the impact of individual losses, and framing investment decisions in terms of long-term objectives rather than short-term fluctuations. Understanding the psychological drivers of risk preferences can help advisors communicate more effectively with clients and manage behavioral biases during market volatility.

Prospect theory has had a transformative impact on finance, leading to the development of behavioral investing strategies, target-date funds, and investor education programs. In the aftermath of market shocks, the insights from this chapter are more relevant than ever, as investors grapple with the emotional impact of losses and the temptation to abandon long-term plans. By embracing prospect theory, modern investors can build more resilient, psychologically informed portfolios.

Chapter 28: Bad Events

"Bad Events" is a key chapter because it explores the disproportionate psychological impact of negative outcomes on decision making. Kahneman demonstrates that losses and bad events carry much more weight in our minds than equivalent gains or good events, a phenomenon that underpins loss aversion and risk-averse behavior.

The chapter presents research showing that people require substantially larger gains to offset the psychological pain of losses. Kahneman discusses experiments where participants react more strongly to negative feedback or losses than to positive outcomes. He explains that this asymmetry affects everything from investment decisions to personal relationships. The chapter also explores the evolutionary roots of our sensitivity to bad events, suggesting that it may have conferred survival advantages in the past.

For investors, the practical takeaway is to recognize and manage the emotional impact of losses. Implementing systematic risk controls, such as stop-loss orders and diversification, can help mitigate the effects of bad events. Investors should also avoid making decisions in the heat of negative emotions and should review performance over longer time horizons to smooth out the impact of short-term setbacks.

Historical market corrections and crashes provide ample evidence of the power of bad events to shape investor behavior. The panic selling during the 2008 financial crisis, for example, was driven in part by the overwhelming psychological weight of losses. In modern markets, where volatility is amplified by technology and media, understanding the impact of bad events is essential for maintaining discipline and long-term perspective.

Chapter 35: Two Selves

This chapter is critically important because it introduces the concept of the experiencing self and the remembering self—two distinct ways of perceiving happiness, satisfaction, and well-being. Kahneman argues that these selves often have conflicting priorities, leading to decisions that optimize for memorable experiences rather than sustained happiness.

Kahneman uses examples from vacations, medical procedures, and financial outcomes to demonstrate how the remembering self constructs narratives based on the most intense and final moments of an experience (the peak-end rule), while the experiencing self lives in the present. He explains that duration neglect—the tendency to ignore the length of an experience—can lead to distorted memories and suboptimal choices. The chapter provides data showing that people often choose options that make for better stories, even if they are less enjoyable in the moment.

For investors, this insight is invaluable for aligning investment strategies with genuine goals. Rather than chasing memorable wins or avoiding memorable losses, investors should focus on long-term objectives and overall satisfaction. Regularly reviewing performance in terms of progress toward goals, rather than episodic highs and lows, can help maintain discipline and avoid regret-driven decisions.

The two-selves framework has broad implications for financial planning, retirement strategies, and goal setting. In an era of constant performance tracking and social comparison, the tension between the experiencing and remembering selves is more pronounced than ever. By understanding this distinction, investors can make choices that enhance both present and future well-being, leading to more fulfilling financial lives.

Practical Investment Strategies

- System 2 Activation Before Major Decisions: Before executing significant trades or portfolio shifts, investors should implement a deliberate pause to engage System 2 thinking. This means stepping back from gut reactions, reviewing all available data, and asking probing questions about assumptions and risks. Action steps include using a pre-trade checklist, soliciting counterarguments from colleagues, and forcing oneself to write a brief investment thesis before acting. This approach reduces impulsive errors and ensures that analytical reasoning tempers intuition.

- Bias Mitigation Through Decision Journals: Maintaining a decision journal is a powerful tool for exposing and mitigating cognitive biases. Investors should record the rationale, context, and emotions behind each major decision, along with expected outcomes. By periodically reviewing these entries, patterns of bias—such as overconfidence, anchoring, or availability—become apparent. Over time, this process fosters self-awareness and continuous improvement, helping investors refine their judgment and avoid repeating mistakes.

- Diversification to Counteract Overconfidence: Overconfidence often leads investors to concentrate portfolios in a few favored assets or sectors. To combat this, investors should adopt a disciplined diversification strategy, spreading risk across uncorrelated assets. Tools such as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) can quantify concentration, while portfolio optimization software can suggest optimal allocations. Regular reviews ensure that diversification remains aligned with long-term objectives, reducing the impact of unforeseen events and cognitive blind spots.

- Pre-Commitment and Rule-Based Investing: To minimize the influence of emotional reactions and framing effects, investors can establish pre-defined rules for buying, selling, and rebalancing. Examples include setting stop-loss orders, rebalancing on a fixed schedule, or using quantitative screens for stock selection. By committing to rules in advance, investors sidestep the temptations of market timing and narrative-driven decisions, enhancing consistency and discipline.

- Scenario Analysis and Stress Testing: Incorporating scenario analysis into the investment process helps counteract the illusion of understanding and prepares portfolios for a range of potential outcomes. Investors should routinely model best-case, worst-case, and base-case scenarios, considering both probabilistic and qualitative factors. Stress testing portfolios against historical crises (e.g., 2008, 2020) reveals vulnerabilities and informs risk management strategies.

- Anchoring Awareness and Multiple Valuations: To avoid anchoring on arbitrary price targets or consensus estimates, investors should use multiple valuation methods—such as discounted cash flow (DCF), comparable company analysis, and historical multiples. Comparing results across methodologies reduces reliance on any single anchor and encourages more objective decision making. Documenting the rationale for chosen valuation ranges further guards against unconscious bias.

- Loss Aversion Management Through Framing: Investors can reframe losses as part of a broader, long-term process rather than isolated failures. This involves setting clear, long-term goals and evaluating performance over extended periods. Tools such as rolling returns analysis and goal-based reporting help contextualize short-term setbacks, reducing the emotional impact of losses and supporting more rational decision making.

- Behavioral Coaching and Accountability Partnerships: Engaging with a trusted advisor, mentor, or peer group can provide an external check on cognitive biases and emotional reactions. Regular meetings to review decisions, challenge assumptions, and discuss lessons learned foster accountability and continuous learning. Behavioral coaching is especially effective during periods of market stress, when biases are most likely to surface.

Modern Applications and Relevance

The principles outlined in "Thinking, Fast and Slow" are more relevant than ever in today’s investment landscape. The explosion of information, the rise of algorithmic trading, and the proliferation of behavioral data have amplified both the opportunities and the pitfalls identified by Kahneman. Investors now operate in an environment where cognitive biases can be exploited by sophisticated algorithms, and where emotional reactions are magnified by social media and market volatility.

Since the book’s publication, the field of behavioral finance has become mainstream, influencing everything from investment product design to regulatory policy. Robo-advisors now incorporate behavioral nudges, such as automatic rebalancing and loss-framing, to help investors stay disciplined. Financial advisors are trained to recognize and manage client biases, using tools inspired by Kahneman’s research. The core message—that human judgment is systematically flawed but improvable—has shaped the way modern investors approach risk, diversification, and decision making.

At the same time, some aspects of the market have changed. Big data and machine learning have enabled more sophisticated analysis, but they also introduce new cognitive traps, such as the illusion of understanding complex models or overfitting to historical data. The sheer volume of information can exacerbate availability bias, while the speed of trading increases the risk of System 1-driven errors. However, the timeless lessons of Kahneman’s work—such as the need for humility, structured processes, and ongoing learning—remain as vital as ever.

Modern examples abound: during the COVID-19 market crash, loss aversion and availability bias led many investors to panic sell, only to miss the rapid recovery. The GameStop saga illustrated the power of narrative, social proof, and availability in driving herd behavior. Meanwhile, institutional investors increasingly use scenario analysis and behavioral audits to identify and mitigate biases in their processes. By adapting Kahneman’s classic advice to today’s tools and challenges, investors can navigate an ever-changing landscape with greater confidence and resilience.

Most investors waste time on the wrong metrics. We've spent 10,000+ hours perfecting our value investing engine to find what actually matters.

Want to see what we'll uncover next - before everyone else does?

Find Hidden Gems First!

Implementation Guide

- Develop Metacognitive Awareness: Begin by cultivating self-awareness around your own decision-making processes. Regularly ask yourself which system—fast or slow—is driving your judgments. Use prompts such as, “Am I relying on intuition or analysis?” and “What assumptions am I making?” This habit forms the foundation for identifying and correcting cognitive biases.

- Establish Structured Decision Processes (1-3 Months): Build a repeatable process for all major investment decisions. This includes creating a pre-trade checklist, maintaining a decision journal, and setting up periodic review meetings. Within the first quarter, aim to document every significant decision, noting the rationale, data sources, and emotional state at the time. Over time, this record will reveal patterns and areas for improvement.

- Construct a Diversified Portfolio (3-6 Months): Use behavioral insights to inform portfolio construction. Allocate assets across uncorrelated classes, avoiding concentration in familiar or “hot” sectors. Apply tools such as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index to monitor diversification. Set clear, long-term objectives and align your allocation with your risk tolerance, time horizon, and behavioral tendencies.

- Implement Ongoing Bias Audits (Quarterly): Schedule quarterly reviews of your investment decisions and performance. Look for recurring biases, such as anchoring, overconfidence, or loss aversion. Use scenario analysis and stress testing to challenge assumptions and prepare for a range of outcomes. Adjust your process and strategies based on lessons learned, seeking feedback from trusted advisors or peers.

- Pursue Continuous Learning and Improvement (Ongoing): Stay informed about advances in behavioral finance, decision science, and market dynamics. Read books, attend seminars, and engage with professional communities. Incorporate new tools and techniques, such as behavioral coaching, robo-advisors, or advanced analytics, as appropriate. Regularly revisit your goals and processes to ensure they remain aligned with your evolving objectives and market conditions.

--- ---

10+ Free intrinsic value tools

For investors looking to find a stock's fair value, our analytics team has you covered with intrinsic value tools:

📍 Free Intrinsic Value Calculator

📍 Reverse DCF & DCF value tools

📍 Peter Lynch Fair Value Calculator

📍 Ben Graham Fair Value Calculator

📍 Relative Value tool

...and plenty more.

🔍 Explore all these tools for free on the Value Sense platform and start discovering what your favorite stocks are really worth.

FAQ: Common Questions About Thinking, Fast and Slow

1. What is the main takeaway from "Thinking, Fast and Slow" for investors?

The main takeaway is that human decision making is deeply influenced by cognitive biases and mental shortcuts, which can lead to systematic errors in judgment. By understanding the interplay between fast (System 1) and slow (System 2) thinking, investors can recognize when their intuition may be misleading and when to engage in more deliberate analysis. This awareness enables more disciplined, rational investment decisions and helps avoid common pitfalls such as overconfidence, loss aversion, and anchoring.

2. How does Kahneman’s work challenge traditional economic theories?

Kahneman’s research, particularly prospect theory, challenges the assumption that humans are rational actors who always maximize expected utility. He demonstrates that people are loss averse, overweight small probabilities, and are heavily influenced by framing and context. These findings reveal that real-world decision making often deviates from classical models, necessitating new approaches in economics and finance that account for psychological factors.

3. What practical steps can investors take to reduce cognitive biases?

Investors can reduce cognitive biases by implementing structured decision processes, such as using checklists, maintaining decision journals, and conducting regular bias audits. Diversifying portfolios, pre-committing to rules-based strategies, and seeking feedback from trusted advisors also help counteract biases. Embracing probabilistic thinking and scenario analysis further equips investors to navigate uncertainty and avoid overconfidence.

4. Is "Thinking, Fast and Slow" relevant for professional investors and financial advisors?

Absolutely. The book’s insights are foundational for anyone making financial decisions, from individual investors to institutional managers and advisors. It provides tools for understanding client behavior, managing risk, and designing better investment products. The principles of behavioral finance outlined in the book are now widely taught and applied throughout the financial industry.

5. How can the concepts from the book be applied to everyday life outside of investing?

The dual-system model, heuristics, and biases explored in the book are relevant to all forms of decision making, from business and policy to personal choices. By recognizing when intuition may be misleading and when to engage in deliberate thought, individuals can make better choices in areas such as health, relationships, and career. The book’s lessons on happiness and the two selves also offer valuable guidance for setting meaningful goals and improving overall well-being.